科普 | 什么是群体免疫?这是切实可行的解决方案吗?

What is herd immunity and could it slow the spread of coronavirus COVID-19 around the world?

By Rebecca Armitage and Jack Hawke in London

Updated Thu at 8:45am

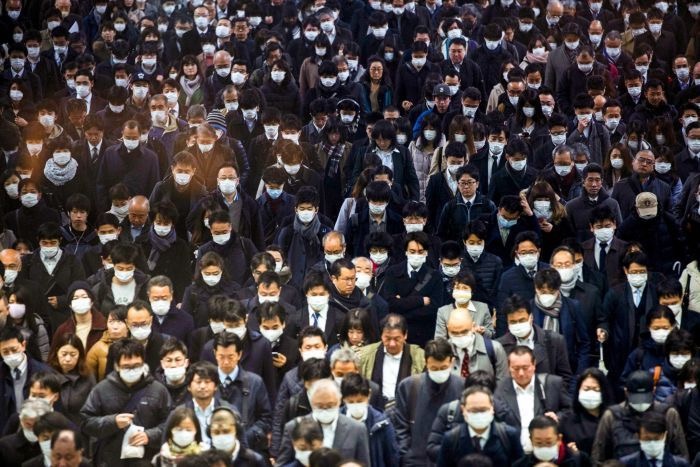

Photo: Some governments, including the UK and the Netherlands, have discussed pursuing herd immunity to combat coronavirus. (Reuters: Athit Perawongmetha)

Photo: Some governments, including the UK and the Netherlands, have discussed pursuing herd immunity to combat coronavirus. (Reuters: Athit Perawongmetha)

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to worsen, some governments have started discussing how "herd immunity" could be used to stop the virus in its tracks.

The UK's chief science adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, said on March 13 that one of "the key things" Britain needed to do was "build up some kind of herd immunity so more people are immune to this disease and we reduce the transmission".

Sweden has made tests available only for hospital staff and at-risk groups.

"Our main purpose now is to slow down the spread of infection as much as possible, and build up some kind of immunity in society," the country's chief epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, said.

And while Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte has closed schools and restaurants, he says a total lockdown in his country probably won't work.

Instead he says the Netherlands is looking at a "controlled distribution" of COVID-19 "among groups that are least at risk".

But not everyone is happy about this approach, with some scientists in the UK and Australia describing it as a dangerous farce.

Herd immunity can stop an outbreak

Herd immunity means that a large portion of a population becomes infected with a disease, but many recover and are then immune to it.

An outbreak eventually fizzles out because there are fewer viable hosts for the virus to infect.

It's considered one of the main ways to fight an outbreak, along with extreme isolation measures, testing and tracing potential cases, and developing a vaccine.

Historians believe the second wave of the Spanish flu pandemic in mid-1918 was the most devastating because few people became immune to it during the first wave.

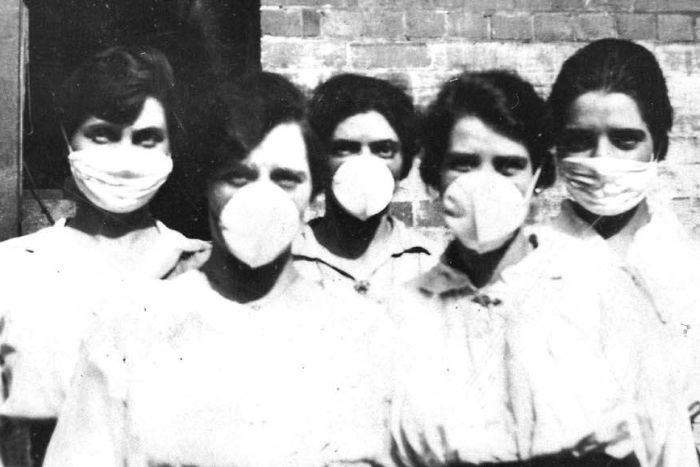

PHOTO: There were multiple waves of the Spanish Flu outbreak over several years. (State Library of Queensland)

PHOTO: There were multiple waves of the Spanish Flu outbreak over several years. (State Library of Queensland)

Britain's chief science advisor said herd immunity would prevent a similar situation if coronavirus was to disappear but then re-emerge.

Sir Patrick said 60 per cent of Britons — or at least 36 million people — would need to catch COVID-19 for this to work.

The UK Government was eventually forced to backpedal on these comments after an outcry from scientists.

"Herd immunity is not our goal or policy, it's a scientific concept. Our policy is to protect lives and to beat this virus," Health Secretary Matt Hancock said.

Could herd immunity work for coronavirus?

Scientists have been quick to point out that it's not yet known whether people who survive COVID-19 are then resistant to it.

Japanese authorities said on March 16 that a man who recovered from the disease tested positive for COVID-19 again several weeks later.

PHOTO: A man who recovered from coronavirus during the Diamond Princess quarantine tested positive again two weeks later, according to Japanese authorities. (Reuters via Kyodo)

PHOTO: A man who recovered from coronavirus during the Diamond Princess quarantine tested positive again two weeks later, according to Japanese authorities. (Reuters via Kyodo)

That could have been a testing error.

But Diego Silva, a lecturer in bioethics at the University of Sydney, says we still don't know everything about this virus and the body's response to it.

"Allowing a virus to spread in your country when you don't know whether, or how long it takes for, people to become susceptible a second time to the COVID-19 virus is a risk," he said.

Herd immunity also accepts that some people will die

When discussing herd immunity, the Dutch Prime Minister said vulnerable people would need to be protected.

"This assumes you can actually shield those at risk in the first place, and it's not clear to me that you can," Dr Silva warns.

PHOTO: Public health experts say letting the virus infect healthy, strong people puts older, vulnerable people at great risk. (Reuters: Hannah McKay)

PHOTO: Public health experts say letting the virus infect healthy, strong people puts older, vulnerable people at great risk. (Reuters: Hannah McKay)

Scientists have pointed out that if COVID-19 is allowed to spread, there will be fewer younger people to look after the vulnerable.

"Intentionally allowing the virus to spread requires accepting that people will die in the short term, in part due to hospitals and the health system being overwhelmed," Dr Silva says.

British virologist Professor John Oxford from Queen Mary University of London said letting the virus spread also takes governments into murky ethical waters.

"As a virologist, I'm totally unnerved by it. I don't like it, I say it's got a touch of eugenics, which I'm frightened about," he says.

"I feel nerve-wracked about it, I think it's kind of a huge experiment when you're indulging letting the virus go like this, rip through the community. People will die. What will their relatives say?

"The whole thing is a bit of a farce — and a dangerous farce."

The UK has abandoned its more relaxed approach to coronavirus after researchers warned that 250,000 people would die as a result.

The Imperial College London told Prime Minister Boris Johnson in a briefing at Number 10 that trying to achieve herd immunity by allowing the virus to spread was unsafe.

So should herd immunity be part of our coronavirus strategy?

Most scientists agree that countries should be trying multiple approaches to contain coronavirus, including social distancing, border controls, and pursuing a vaccine.

PHOTO: The UK has shut down mass gatherings after researchers warned that allowing them to continue could kill 250,000. (Reuters: John Clifton)

PHOTO: The UK has shut down mass gatherings after researchers warned that allowing them to continue could kill 250,000. (Reuters: John Clifton)

"With any infectious disease, particularly respiratory ones such as coronaviruses, a primary public health goal is herd immunity," says Dr Silva.

But Dr Silva says a vaccine, which could be 18 months away, is one of the best and safest ways to do that.

"One thing is to introduce a vaccine to build up community resistance with an eye toward herd immunity. The other is to let a gnarly virus happily spread about," he says.

"With a vaccine, there isn't the element of sacrificing a segment of your people."

University of Sydney Bioethics Professor Angus Dawson says the herd immunity debate is confusing people, and governments should instead focus on "coordinated action".

"We should instead be introducing much more rigorous social distancing than we have seen so far," he says.

"This pandemic is a serious health threat. The protection of the most vulnerable, now, should be the highest priority, not some future theoretical benefit."

Social distancing to protect vulnerable people helps to flatten the curve of the pandemic, spreading the number of infections over a longer period of time.

Not only does this help ensure the healthcare system doesn't become overwhelmed, but it builds up herd immunity in a controlled way over time.

The UK's slow response to the coronavirus outbreak should be a warning to other nations, according to Professor John Oxford.

He says a wartime effort will now be required to avoid a health disaster in Britain.

"It's like the great COVID-19 war. Your grandson will come along and say, 'what did you do in the great COVID war?' and you say, 'I did social distancing, I cut holidays', and you contributed," he says.

"If 50 million people contribute like that, I think we can wipe the virus out."