气泡纸的意外发明

The Accidental Invention of Bubble Wrap

Two inventors turned a failed experiment into an irresistibly poppable product that revolutionized the shipping industry

By David Kindy

When a very young Howard Fielding carefully cradled his father’s unusual invention, he had no idea that his next action would make him a trendsetter. In his hands was a plastic sheet with air-filled bumps across it. As he fingered the funny-feeling film, he couldn’t resist the temptation: he started popping the bubbles—just like much of the rest of the world has been doing ever since.

And so Fielding, who was about 5 years old at the time, became the very first person—for fun—to pop Bubble Wrap. The invention revolutionized the shipping industry and made the e-commerce era possible, protecting billions of products shipped worldwide each year.

“I remember looking at the stuff and my instinct was to squeeze it,” Fielding says. “I say I’m the first person to pop Bubble Wrap, but I’m sure it’s not true. The adults at my father’s firm likely did so for quality assurance. But I was probably the first kid.”

He adds with a chuckle, “They were really fun to pop. The bubbles were a lot bigger then, so they made a loud noise.”

Fielding’s father Alfred was co-inventor of Bubble Wrap with his business partner Marc Chavannes, a Swiss chemist. They were trying to create a textured wallpaper in 1957 that would appeal to the burgeoning Beat generation. They put two pieces of plastic shower curtain through a heat-sealing machine but were disappointed—at first—by the results: a sheet of film with trapped air bubbles.

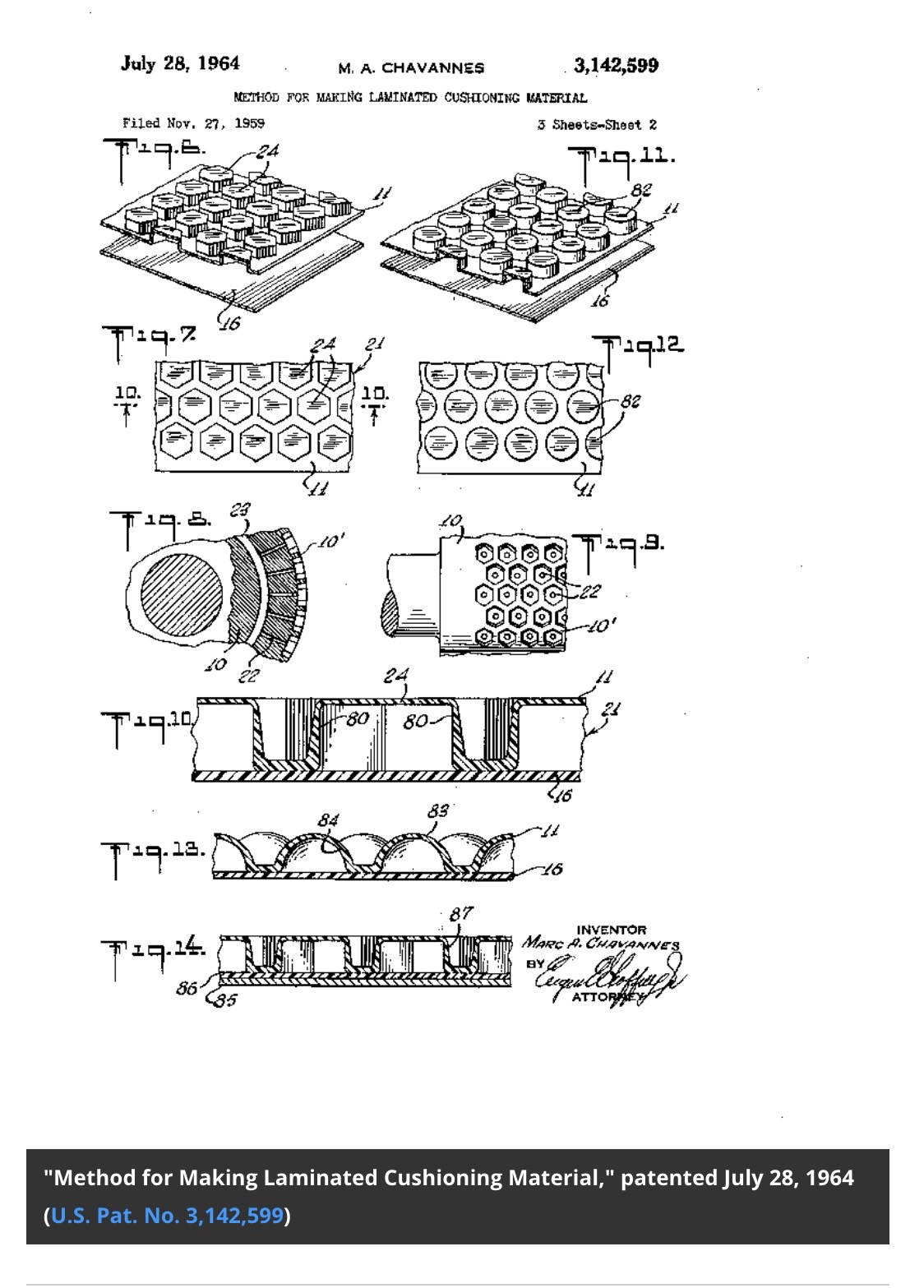

However, the inventors did not totally dismiss their failure. They were granted the first of several patents for the process and equipment of embossing and laminating materials, then started thinking of uses: more than 400, in fact. One—greenhouse insulation—made it off the drawing board, but ultimately was about as successful as textured wallpaper. The product was actually tested in greenhouses, but it proved ineffective.

To continue developing their unusual product, which was branded Bubble Wrap, Fielding and Chavannes founded Sealed Air Corp. in 1960. It wasn’t until they decided the next year to use it as packaging material that they found success. IBM had recently introduced the 1401 unit—considered the Model-T of the computer industry—and needed a way of protecting the delicate device during transit. The rest, as they say, is history.

“It was the answer to IBM’s problems,” says Chad Stephens, vice president of innovation and development for Sealed Air’s Product Care Division. “They could ship their computers without damage. That opened the door for a lot of other businesses to start using Bubble Wrap.”

Small packaging companies quickly embraced the new technology. To them, Bubble Wrap was a godsend. Previously, the best way to protect an item during shipping was to surround it with balled up newsprint. It was messy since ink from the old newspapers often rubbed off on the product and those handling it. Plus, it really didn’t offer that much protection.

Sealed Air began to grow as Bubble Wrap caught on. The product evolved into different shapes, sizes, strengths and thicknesses for expanded uses: big and little bubbles, wide and short sheets, large and short rolls. All the while more people were discovering the joy of popping those air-filled pockets (even Stephens admits to being a “stress-relief popper”).

Still, the company wasn’t turning a profit. That’s when T.J. Dermot Dunphy became CEO in 1971. He helped build annual sales from $5 million in his first year to $3 billion in 2000 when he left the firm.

“Marc Chavannes was a visionary and Al Fielding was a first-class engineer,” says Dunphy, who at 86 years young still works every day at his private equity investment and management firm, Kildare Enterprises. “But neither wanted to run the company. They just wanted to work on their inventions.”

An entrepreneur by training, Dunphy helped Sealed Air stabilize its operation and diversify its product base. He even expanded the brand into the swimming pool industry. For several years, Bubble Wrap pool covers were extremely popular. With large air pockets, the covers helped trap solar rays and retain heat so pool water remained warm, although these bubbles weren’t poppable. The firm eventually sold the line.

Barbara Hampton, Howard Fielding’s wife who coincidentally is a patent information specialist, is quick to point out how patents enabled her father-in-law and his partner to do what they did. In all, they were granted six patents for Bubble Wrap, most of which dealt with the process for embossing and laminating plastic and the necessary equipment. In fact, Marc Chavannes received two earlier patents for thermoplastic film, but probably didn’t have poppable bubbles in mind when he did. “A patent provides a creative person with the opportunity to reap the rewards of his ideas,” Hampton says.

Today, Sealed Air is a Fortune 500 company with sales of $4.5 billion in 2017 and 15,000 employees serving customers in 122 countries. Originally located in New Jersey, the business moved its world headquarters to North Carolina in 2016. It produces and sells several products, including Cryovac, a thin plastic that is shrink-wrapped around food and other items. Sealed Air even offers an airless Bubble Wrap that is less expensive to ship to customers.

“It’s an inflatable version,” Stephens says. “Instead of large rolls of air, we sell rolls of tightly wrapped film with a mechanical unit that adds the air when needed. It’s a lot more efficient.”

更多精彩详细内容请关注小译号 Smithsonian Magazine