为什么雕像如此有影响力?

Black Lives Matter protests: Why are statues so powerful?

By Kelly Grovier

After statues around the world were defaced as part of the Black Lives Matters protests, Kelly Grovier looks at why some monuments provoke powerful reactions.

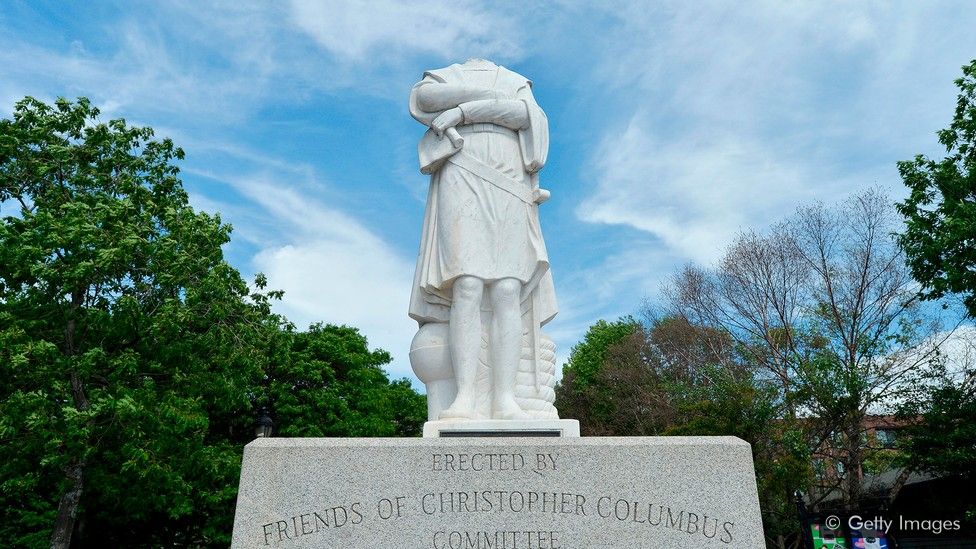

What are statues for? The recent destruction of monuments in Britain and the US – from the toppling in Bristol, England, last weekend of a bronze sculpture commemorating the 18th-Century British slave trader Edward Colston, to the defacement this week in Boston, Miami and Virginia of statues venerating Christopher Columbus and Confederate leaders – raises intriguing questions about the very purpose of public statuary. Why are we compelled to create such likenesses in the first place?

The defacements in the US and the de-pedestaling of Colston, whose effigy was roughly rolled through the city streets by Black Lives Matter supporters before being dumped in a harbour, comes in the wake of the murder last month in Minneapolis, Minnesota, of an African-American, George Floyd, by a white police officer, who killed Floyd by kneeling on his neck. Floyd’s slow eight-minute asphyxiation, captured on video by a passerby, has prompted passionate protests across the world and has added fresh urgency to campaigns demanding the removal of statues that glorify figures whose reputations (and fortunes) were built on the crushing of peoples of colour and the stifling of indigenous cultures.

In recent years, several monuments in the US that commemorate military and political leaders of the defeated southern Confederacy (which fought to preserve slavery in the 1860s) have been dismantled or relocated, whisked away from public view. The fall of Colston in Britain is part of a fresh wave of expeditious extractions washing across the West. Earlier this week, Columbus was not only beheaded in Boston but torn down by ropes both in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and in Richmond, Virginia, where the 15th-Century explorer’s effigy was dragged to a nearby pond and drowned, Colston-style. A makeshift tombstone that read ‘Racism, you will not be missed’ was placed at the water’s edge.

Fearing the acceleration of similar purgings in the UK, leaders across the political spectrum raced to denounce the destruction of Colston’s statue and to caution against the ripping down of any others. In a rare instance of synchronised messaging, the UK’s Conservative Home Secretary Priti Patel and the leader of the opposition, Labour’s Sir Keir Starmer, agreed that the attacks should be condemned, as thousands gathered in Oxford to demand the removal from Oriel College of a stone statue of Cecil Rhodes, a British supremacist who enriched himself by exploiting Africa’s people and resources. At the time of writing, Rhodes’ statue, which stares through a protective mesh like a captured beast, still teeters in the balance – inviting the world to reflect on what the appropriate fate for such relics of imperial plunder ought to be.

To answer that question, perhaps it’s worth considering why statues exist in the first place and how we are hardwired to connect with them. The earliest-known material likeness of a human being, a small statuette of a female body discovered in a cave in Germany’s Swabian Forest in 2008, may offer clues about the essence of our impulse to create such things. A mere 6cm (2.4in) in height and carved from woolly mammoth tusk 40,000 years ago, the so-called Venus of the Hohle Fels crudely exaggerates the features of a woman’s body and is thought to have served as a fertility totem.

From their earliest inception, statues were less about the individuals they depict than about how we see ourselves

But it is not what the figurine, which demanded hundreds of hours of patient scraping to carve, depicts that is ultimately so revealing, but what it neglects to portray. The prehistoric craftsman who slowly sculpted this hunk of ivory into shape made the extraordinary aesthetic decision to leave the object without a head. Where the neck should be, a small eye-hook loop, through which a string or strip of leather could be threaded, has been painstakingly sculpted. Dangling from a necklace, the statue’s head is that of its wearer, who imaginatively completes the figurine by merging with it. From their earliest inception, in other words, statues were as much conceptual as they were material – less about the individuals they depict than about how we see ourselves.

Just how engrained that instinct is – to perceive an aspect of oneself in the image of another – is impossible to measure. Such an impulse may explain why it is so agonisingly difficult to tolerate the persistence of memorials that venerate past masters of pain. Theirs is a suffocating weight. The outrage that many feel about having to share the streets with such hulking ghosts of oppression is deep and crushingly real. To address the thorny issue of how best to handle monuments whose aura an appreciable proportion of society finds toxic, countries have begun to adopt a variety of different strategies.

In London, the capital’s mayor, Sadiq Khan, has announced the convening of a special commission to debate the dismantling (and erection) of the city’s statues. In the US on Wednesday, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, hoping to pre-empt a violent plundering of Capitol Hill, called for the swift removal of 11 statues that commemorate Confederate leaders. “The statues in the Capitol should embody our highest ideals as Americans, expressing who we are and who we aspire to be as a nation,” said the California Democrat in a statement, explaining her decision. “Monuments to men who advocated cruelty and barbarism to achieve such a plainly racist end are a grotesque affront to these ideals. Their statues pay homage to hate, not heritage. They must be removed.”

Is amputation the best cure for this disease? The problem, of course, in submerging mementos of a painful past in the nearest body of water is things, especially painful things, have a tendency to re-emerge from the murky deep. The British street artist Banksy, whose own work routinely dredges the shallows of society’s intolerance and forces us to confront uncomfortable shapes of hypocrisy and inequality, proposed this week an ingenious solution to the quandary that society finds itself in. “What should we do with the empty plinth in the middle of Bristol?”, Banksy asked in a post on his Instagram account. “Here’s an idea that caters for both those who miss the Colston statue and those who don’t. We drag him out the water, put him back on the plinth, tie cable round his neck and commission some life size bronze statues of protestors in the act of pulling him down. Everyone happy. A famous day commemorated.”

As Banksy’s accompanying drawing (which wittily imagines a precariously repositioned Colston, faltering forever on the verge of collapse) suggests, what’s tricky is finding the right balance when ‘catering’ to the diverging perspectives of everyone in society who must bear the weight of a statue. In Germany, where decisions long ago had to be taken about how the Nazi era would be fossilised in the material memory of the nation’s streets and squares, it was resolved that erasing the past was not an option. Rather than polluting the municipal air with monuments to the perpetrators of pain, however, efforts have been made to preserve instead memorials that honour the fortitude of Hitler’s victims. Perhaps we should think of statues the way we think of trees. When one is found to be disfigured by disease we should resolve to plant a fresh copse, one that cleanses the atmosphere and doesn’t choke our breath.