为什么原谅前任这么难?

Why is it so hard to forgive an ex?

By Chermaine Lee

Break-ups are never easy, but why do some people fight to win an ex back while others run a mile? The temptation to rekindle an old flame is deeply rooted in our psychology.

Tears streamed down her face, as Yannes told George their relationship was no longer working out. Along the promenade, the 28-year-old from Hong Kong heaved a sigh of relief and slowly walked back home, with her heart broken.

It was the third time the two had broken up in just the course of two months. This time, Yannes said there was no way back.

“I missed him a lot and I constantly replayed our happy memories in my mind,” says Yannes of each of their previous break-ups. The nostalgia for their happier times soon got the better of her “so I went back again and again. But our mindsets are too different to begin with and that hasn’t changed. I’ve deleted his presence on all my social media, and I just know that this is the last time we will be together.”

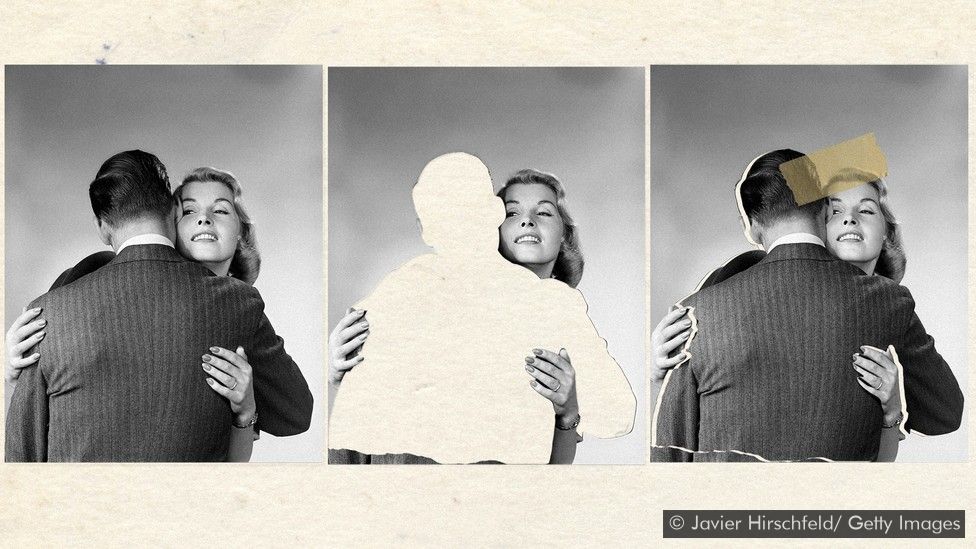

The desire to rekindle an old flame turns out to be quite common throughout our lifetimes. Almost two-third of college students have had an on-again/ off-again relationship, while half will continue a sexual relationship after a break-up.

The blurriness of relationships continues even after vows have been exchanged. Over one-third of cohabiting couples and one-fifth of married couples have experienced a break-up and renewal in their current relationship.

A feeling that has inspired countless songs, novels, plays, reality shows and films – breaking up and seeking forgiveness is perhaps unsurprisingly deeply rooted in our psychologies. But why are we prone to rehash a relationship that failed?

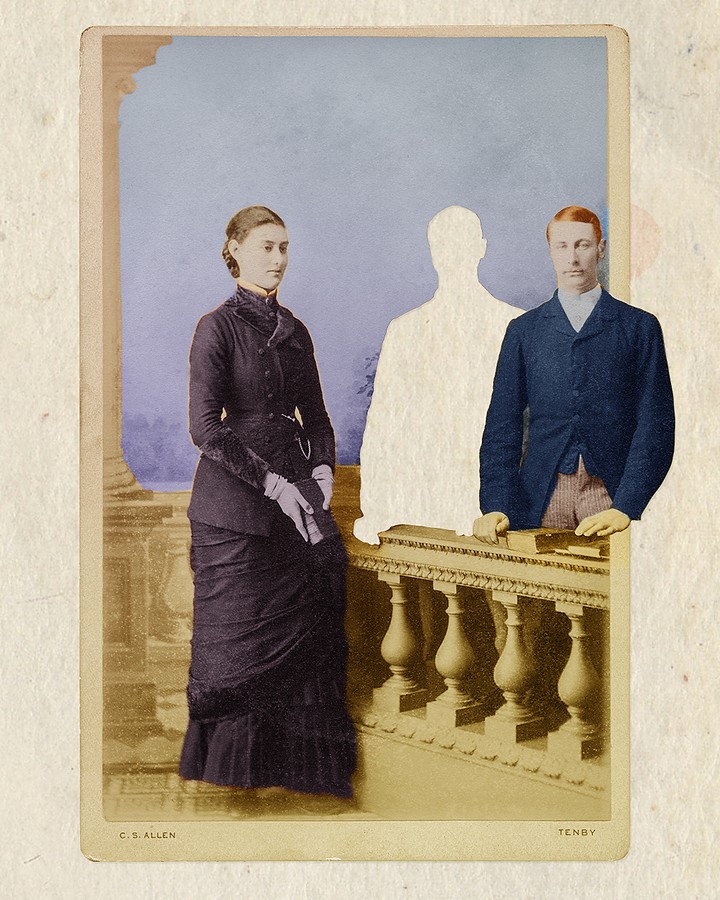

When the break-up first happens, people tend to go through what Helen Fisher, a neurologist at the Kinsey Institute, calls a “protest” phase, during which the rejected party becomes obsessed with winning back the person who calls it quits.

Fisher and a group of scientists put 15 people who were recently rejected by a romantic partner through a brain scan, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). When they were told to look at the image of their former beloved, the areas in their brain associated with gains and losses, craving and emotion regulation were activated, as well as brain regions for romantic love and attachment.

After rejection, you don’t stop loving that person; in fact, you can love that person even more – Helen Fisher

“After rejection, you don’t stop loving that person; in fact, you can love that person even more. The major brain region associated with addiction is active,” Fisher says.

At this moment, the rejected lovers experience elevated levels of dopamine and the neurotransmitter norepinephrine, which is linked to raised stress levels and the urge to call for help, according to Fisher. She calls this “frustration attraction”. This is thought to be why, in a moment of high emotions, some spurned people resort to dramatic gestures to get back together with the object of their desire.

Active in both the rejected men and women was the nucleus accumbens, a major brain region associated with addiction. The participants in Fishers study thought about their rejecter “obsessively” and craved emotional union with that partner.

“The separation anxiety is like a puppy taken away from its mother and put in the kitchen by itself: it runs around in circles, barks and whines,” Fisher adds. “The couples who break up and get back together multiple times are still chemically addicted to each other, so they are not able to cleanly split until that [addiction] runs out.”

As well as the chemical reactions in our brain, people push to renew their once-doomed relationships because of a whole host of behavioural reasons. If a partner has dated someone new after the split this can speed up the erasure of old feelings, reducing the likelihood of getting back together. While other people experience more synchronised levels of passion after the break-up, increasing their likelihood of forgiveness, and so on.

A sense of unresolvedness in the relationship could make it tempting for the partners to try it out again, says Rene Dailey, a professor who researches on-again/off-again relationships at the University of Texas.

“The couple might experience a lot of conflict [during] the break-up but still feel connected or love for their partner,” says Dailey. “So it could be more about not being able to manage or resolve the conflict. If the break-ups are ambiguous, people might feel like they made positive changes to the relationship and try again.”

Dailey also says attachment theory, popular is some areas of psychology and much covered in the media to explain some parts of compatibility in dating, does not explain romantic reconciliation.

Attachment theory suggests that caregivers’ behaviour towards children shapes their attachment style in their adult life – they can be secure, anxious or avoidant towards other adults later on. A secure attachment style signifies a healthy emotional communication, while anxiously-attached individuals tend to doubt their self-worth and go to great lengths to restore proximity. A third group, those with avoidant attachment, are perceived as emotionally unavailable and self-sufficient by defensively refusing proximity.

According to this theory, partners with anxious and avoidant attachment styles are said to be attracted to each other and find it difficult to break up permanently. But, research appears not to support this.

“We found very little differences between on-off and non-cyclical partners in attachment anxiety and avoidance, nor differences in how these attachment orientations are related to relational quality for such partners. Even though attachment theory seems like a good explanation, we haven’t found this to be the case,” says Dailey.

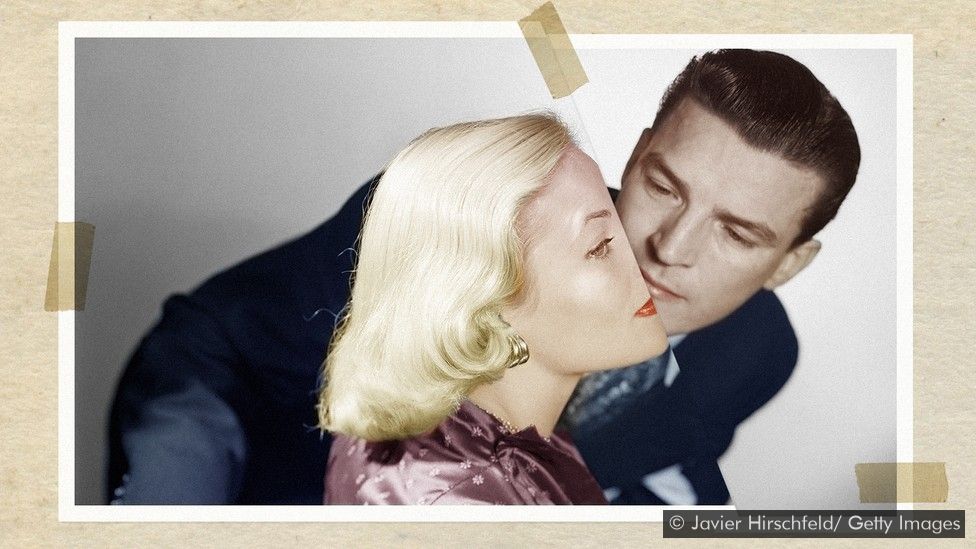

Like with Yannes, nostalgia and loneliness do play a role in pursuing forgiveness. “When people do find themselves wanting to get back together with an ex even if they didn’t treat them well, it is usually related to feelings of loneliness, missing the positive things about the relationship, and the sense of loss and grief that comes with a break-up,” says Kristen Mark, a professor specialising in sexual health at the University of Kentucky. She says that nostalgia for past relationships often first emerges when the current relationship quality begins to suffer.

Those with a stronger fear of being single report a greater longing for their ex-partners and a stronger desire to renew the relationship. This might also explain Yannes’s behaviour in the current climate. She says she felt lonely during the coronavirus outbreak, prompting her to reach out to her previous lover and attempt to mend their relationship.

The loneliness that locked-down single people are feeling could be exacerbated by social media, as it makes it easier for one to keep their ex-lovers in sight. The desire to avoid loneliness at all costs can drive people back in the arms of their ex-partners, according to Gail Saltz, an associate professor of psychiatry at the New York Presbyterian Hospital Weill-Cornell School of Medicine.

We tend to see past relationships in a rosier light than they necessarily were – Gail Saltz

“The invention of Facebook and other social media sites enable people to find old exes and bring them together,” says Saltz. “We tend to see past relationships in a rosier light than they necessarily were and forget that people can change over time as well. Social media makes it harder to have closure and move on – stalking an ex’s posts can be very unhealthy.”

With social media making separations stickier, it is perhaps unsurprising that Millennials and Gen Z could be even more susceptible to negative break-up behaviours, according to Berit Brogaard, a professor at the University of Miami who specialises in the philosophy of emotions and authored the book On Romance.

“Bad break-up behaviours have been around for as long as romantic love has,” says Brogaard. “But that has become so prevalent that they have been categorised and named – ghosting, submarining, benching, bread-crumbing, orbiting, zombieing and so on.”

Younger Millennials and Gen Zs are much more vulnerable to anxiety and depression and depend much more strongly on social approval than older Millennials, so the former may well be prone to on-again/ off-again relationships, Brogaard added.

If Millennials and Gen Zs are born with laptops and tablets on their hands, they tend to look for dating solutions online. As a result, personal coaching businesses in the US alone were valued at more than $1bn (£0.8bn) in 2018 and a niche market for the heartbroken has started to emerge. Break-up coaches now promise to help their clients move on or rekindle former romance. Many offer tips and strategies on their blogs, YouTube videos and podcasts which register views in the millions.

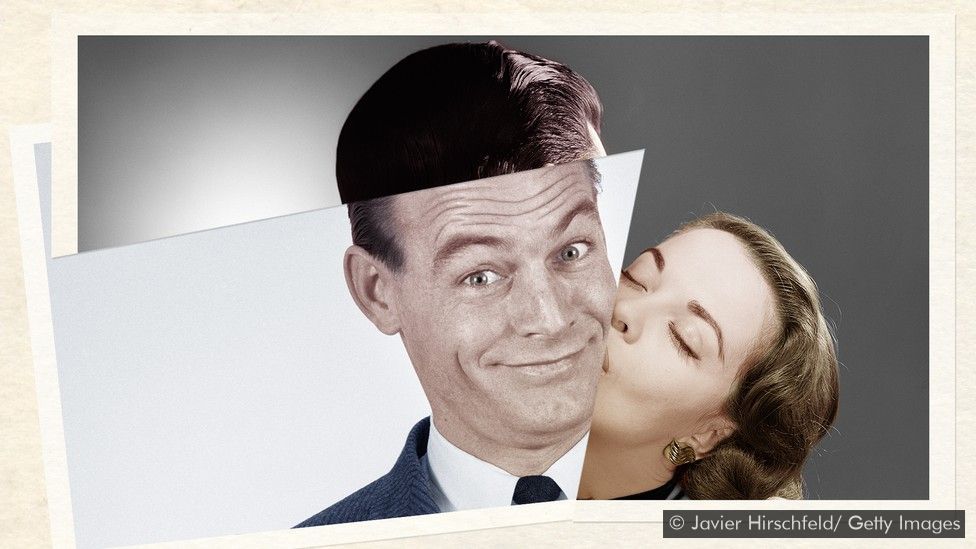

Among some popular ones, a “no-contact rule” (ranging from 30 days to 60 days, some even say infinitely), is a common tactic. This time is supposed to be used to work on self-development. Many suggest sending texts to their exes to remind them of the good times they had and show them how they have changed during this period.

Neurologist and anthropologist Helen Fisher agrees a “no-contact rule” can be beneficial. She says a period of at least 90 days is proven to be effective to abstain from addictive substances. But would this work with relationships?

“The way to accelerate mending a broken heart is similar to treating addiction – you put away their things, stop looking at their social media and have no contact with them,” Fisher says.

Brogaard also says that the rule “does have some basis in science”. The intensity of strong emotions – including anger, betrayal and so on – tends to lessen with time.

Lilian, another Hong Konger in her late 20s, was one of the heartbroken internet users who searched for ways to reconcile with her ex boyfriend on the internet a few days after a break-up. She bumped into a dating coach’s videos on social media.

Lilian says that the coach offered tips to create distance with the ex-partner and work on re-attraction. “It comforted me after the separation, but it also made me more anxious. The break-up coach suggested waiting for 30 days to contact the ex-boyfriend again, and to dress better the next time we meet to show that I have improved myself, but I couldn’t wait that long,” Lilian said.

Although these coaches might come as an instant comfort after a heartbreak, their suggestions might not be scientifically credible. “Break-up coaches tend to lack proper training – self-training or academic – in relevant fields such as neuroscience, psychology, cognitive science, philosophy or social work,” says Brogaard.

The psychologist adds that some even plagiarise others who have relevant training, but they are unable to fact-check the information they lift from others.

“They can be more expensive than a good therapist, but without any evidence that the advice they offer is sound, you might be wasting your time and money buying their products,” she says. “Their books are sometimes more affordable, but not peer-reviewed and are for the most part practically useless.”

They can be more expensive than a good therapist, but you might be wasting your time and money buying their products – Berit Brogaard

Experts still have reservations about the industry, which has little to no regulations. Dailey seconded Brogaard’s comment that a lot of break-up coaches “do not have the qualifications to give advice,” while Saltz says that it’s not a 'regulated area'.

“Pretty much anyone can call themselves a coach. So I’d be very cautious on that front. What amount, intensity and level of formalised training has this person really had? A several day or multi weekend course does not a therapist make. Who trained them, what type of training?” Saltz says.

Brogaard advises the heartbroken to read literature on break-ups and relationships from legitimate sources, including academic review papers on Google Scholar, instead of spending money on break-up coaching. But she warns against spending a lot of time and energy to win someone back.

“If you have to go out of your way to get back with your ex, are they really worth it?”

They said there are no “tricks” to reconciliation but to talk about what went wrong in the failed relationship with honesty.

For those who cannot reconcile with their former romance, the silver linings are that after the “protest” stage, their brain can go into a stage of “resignation/despair”, then finally acceptance, indifference and growth, Fisher says.

“You experience extreme pain and anxiety, but finally there’s recovery,” concludes Fisher. “You never forget the person who dumps you, but you move on and love someone new.”