独来独往对健康有好处?

Why being a loner may be good for your health

By Christine Ro

We tend to decry being alone. But emerging research suggests some potential benefits to being a loner – including for our creativity, mental health and even leadership skills.

This story is featured in BBC Future’s “Best of 2018” collection. Discover more of our picks.

I can be a reluctant socialiser. I’m sometimes secretly pleased when social plans are called off. I get restless a few hours into a hangout. I even once went on a free 10-day silent meditation retreat – not for the meditation, but for the silence.

So I can relate to author Anneli Rufus, who recounted in Party of One: The Loners’ Manifesto:

“When parents on TV shows punished their kids by ordering them to go to their rooms, I was confused. I loved my room. Being there behind a locked door was a treat. To me a punishment was being ordered to play Yahtzee with my cousin Louis.”

Asocial tendencies like these are often far from ideal. Abundant research shows the harms of social isolation, considered a serious public health problem in countries that have rapidly ageing populations (though talk of a ‘loneliness epidemic’ may be overblown). In the UK, the Royal College of General Practitioners says that loneliness has the same risk level for premature death as diabetes. Strong social connections are important for cognitive functioning, motor function and a smoothly running immune system.

This is especially clear from cases of extreme social isolation. Examples of people kept in captivity, children kept isolated in abusive orphanages, and prisoners kept in solitary confinement all show how prolonged solitude can lead to hallucinations and other forms of mental instability.

But these are severe and involuntary cases of aloneness. For those of us who just prefer plenty of alone time, emerging research suggests some good news: there are upsides to being reclusive – for both our work lives and our emotional well-being.

Creative space

One key benefit is improved creativity. Gregory Feist, who focuses on the psychology of creativity at California’s San Jose State University, has defined creativity as thinking or activity with two key elements: originality and usefulness. He has found that personality traits commonly associated with creativity are openness (receptiveness to new thoughts and experiences), self-efficacy (confidence), and autonomy (independence) – which may include “a lack of concern for social norms” and “a preference for being alone”. In fact, Feist’s research on both artists and scientists shows that one of the most prominent features of creative folks is their lesser interest in socialising.

One reason for this is that such people are likely to spend sustained time alone working on their craft. Plus, Feist says, many artists “are trying to make sense of their internal world and a lot of internal personal experiences that they’re trying to give expression to and meaning to through their art.” Solitude allows for the reflection and observation necessary for that creative process.

A recent vindication of these ideas came from University at Buffalo psychologist Julie Bowker, who researches social withdrawal. Social withdrawal usually is categorised into three types: shyness caused by fear or anxiety; avoidance, from a dislike of socialising; and unsociability, from a preference for solitude.

A paper by Bowker and her colleagues was the first to show that a type of social withdrawal could have a positive effect – they found that creativity was linked specifically to unsociability. They also found that unsociability had no correlation with aggression (shyness and avoidance did).

This was significant because while previous research had suggested that unsociability might be harmless, Bowker and colleagues’ paper showed that it could actually be beneficial. Unsociable people are likely to be “having just enough interaction,” Bowker says. “They have a preference for being alone, but they also don’t mind being with others.”

There is gender and cultural variation, of course. For instance, some research suggests that unsociable children in China have more interpersonal and academic problems than unsociable kids in the West. Bowker says that these differences are narrowing as the world becomes more globalised.

Still, it turns out that solitude is important for more than creativity.

Inward focus

It’s commonly believed that leaders need to be gregarious. But this depends – among other things, on the personalities of their employees. One 2011 study showed that in branches of a pizza chain where employees were more passive, extroverted bosses were associated with higher profits. But in branches where employees were more proactive, introverted leaders were more effective. One reason for this is that introverted people are less likely to feel threatened by strong personalities and suggestions. They’re also more likely to listen.

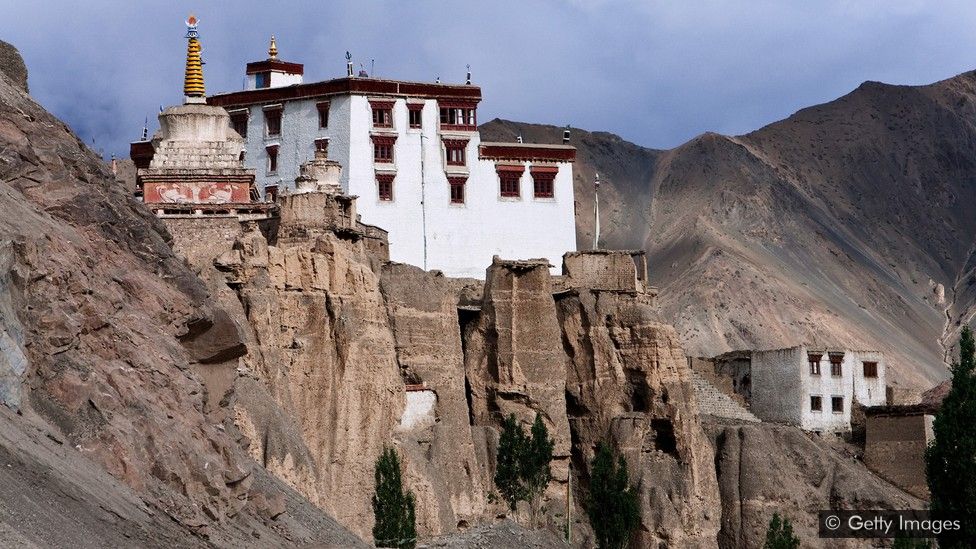

Since ancient times, meanwhile, people have been aware of a link between isolation and mental focus. After all, cultures with traditions of religious hermits believe that solitude is important for enlightenment.

Recent research has given us a better understanding of why. One benefit of unsociability is the brain’s state of active mental rest, which goes hand-in-hand with the stillness of being alone. When another person is present, your brain can’t help but pay some attention. This can be a positive distraction. But it’s still a distraction.

Daydreaming in the absence of such distractions activates the brain’s default-mode network. Among other functions, this network helps to consolidate memory and understand others’ emotions. Giving free rein to a wandering mind not only helps with focus in the long term but strengthens your sense of both yourself and others. Paradoxically, therefore, periods of solitude actually help when it comes time to socialise once more. And the occasional absence of focus ultimately helps concentration in the long run.

A more recent proponent of thoughtful and productive solitude is Susan Cain, author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking and founder of Quiet Revolution, a company that promotes quiet and introvert-friendly workplaces. “These days, we tend to believe that creativity emerges from a decidedly gregarious process, but in fact it requires sustained attention and deep focus,” she says. “Also, humans are such porous, social beings that when we surround ourselves with others, we automatically take in their opinions and aesthetics. To truly chart our own path or vision, we have to be willing to sequester ourselves, at least for some period of time.”

Hermit health

Still, the line between useful solitude and dangerous isolation can be blurry. “Almost anything can be adaptive and maladaptive, depending on how extreme they get,” Feist says. A disorder has to do with dysfunction. If someone stops caring about people and cuts off all contact, this could point to a pathological neglect of social relations. But creative unsociability is a far cry from this.

In fact, Feist says, “there’s a real danger with people who are never alone.” It’s hard to be introspective, self-aware, and fully relaxed unless you have occasional solitude. In addition, introverts tend to have fewer but stronger friendships – which has been linked to greater happiness.

As with many things, quality reigns over quantity. Nurturing a few solid relationships without feeling the need to constantly populate your life with chattering voices ultimately may be better for you.

Thus, if your personality tends toward unsociability, you shouldn’t feel the need to change. Of course, that comes with caveats. But as long as you have regular social contact, you are choosing solitude rather than being forced into it, you have at least a few good friends and your solitude is good for your well-being or productivity, there’s no point agonising over how to fit a square personality into a round hole.