囤起货来,卫生纸和枪支都一样

The real reason people are hoarding toilet paper and guns

BY DEBBIE MILLMAN

I’ve hoarded toilet paper for as long as I can remember. I’ve always felt a bit more secure with a couple of extra packages of mega-rolls in my basement, alongside a 12-pack of paper towels and many six-packs of tissues. My family and friends are sometimes puzzled by this behavior, but mostly, they chalk it up to my long career as a brand consultant and a theory they’ve developed about the pride I have in the products I’ve helped redesign. I wish it were that simple. While it’s true I am loyal to the brands I’ve redesigned—Kleenex tissues; Viva paper towels; Cottonelle, Andrex, and Scott toilet paper—my penchant for paper products is driven more by psychological needs than physiological ones.

Since the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, it seems I am no longer alone in this enthusiastic collection of household staples. In the weeks since coronavirus started spreading across the United States, Americans have rushed to hoard supplies: hand sanitizer, antibacterial wipes, respirator masks, and disposable rubber gloves. This hoarding has resulted in a shortage so severe it has fueled a robust black market for what were once unremarkable household goods. Stockpiling individuals take advantage of the scarcity with exorbitant, opportunistic price gouging.

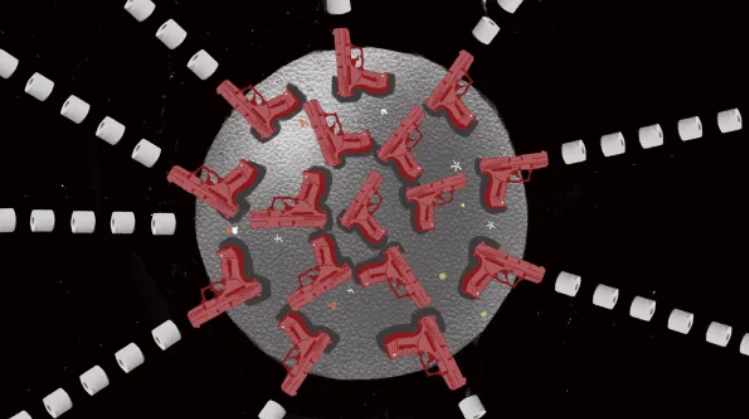

Quotidian paper products are not the only goods experiencing this spike in sales. Firearms are selling at a rapid clip. The FBI reported 3.7 million gun-purchase background checks in the month of March alone, a 41% increase from the month before. It is also the largest number of background checks conducted in a single month since the FBI launched the National Instant Criminal Background Check System in 1998. Both gun and ammunition dealers are now facing a shortage of supplies as customers line the streets in cities across the country, anxious to get into local gun shops, anxious to feel like they might be able to protect themselves and their families.

While firearms and toilet paper might seem unrelated, both appeal to a similar part of our brain. James Watson, the Nobel Prize-winning scientist who helped discover the structure of DNA, described the human brain as the “most complex thing we have yet discovered in our universe.” The three distinct parts of the human brain—the reptilian brain, the mammalian brain, and the neocortex—are considered “sub-brains,” each the result of a distinct age in our evolutionary history. The three brains communicate with each other and intermingle, but these “three brains in one,” (or what is now called a triune brain) are unique to only one species: humans.

The oldest of the three parts of the triune is the reptilian brain. This part of the brain is responsible for all of our vital but involuntary behaviors: the regulation of our metabolism, the digestive system, the adrenalin rush we feel when we believe we may be in danger. We can’t direct these functions; they exist without our ability to control them. The reptilian brain is ignited whenever we feel we might be in danger.

As the world faces an invisible but deadly enemy, a great many of us are regressing to our most primitive selves. We hunker down in our homes, stock up on supplies, and try to protect our families. It’s no surprise some people might want a weapon by their bedside (especially if they’ve recently watched Contagion). But how does having a plethora of toilet paper help us feel safe too?

In 1943, American psychologist Abraham Maslow wrote a paper titled A Theory of Human Motivation, which sought to classify the universal needs of society. He determined that these needs were hierarchical and each need would have to be fulfilled before a person could advance to the next level. The second level of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs—sandwiched between physiological needs and the need for love and belonging—is safety. According to Maslow, humans require the security of body, family, health, and property even more than love. But to reach that second level, we need to fulfill our physiological needs first. These include involuntary behaviors like breathing and excretion. Most people don’t need supplies to help take in air. But almost everyone needs to wipe after they defecate.

Having a stash of guns and toilet paper fulfill both our most primal physiological needs and the need for security and safety. These things provide us with immediate gratification as we search for something tangible to assuage our anxiety. The coronavirus has incited an unparalleled level of uncertainty not only into our individual lives but also the broader culture we are a part of; it has tapped into our deepest fears about the future. The rate of infection is skyrocketing. Hospitals are struggling to be able to care for the most severely afflicted. An estimated 22 million people are unemployed. The economy has come to an abrupt halt.

At a time when we feel completely out of control and entirely at risk, we’re reaching out for something, anything to hold on to. We are desperate to find comfort in what we believe will protect us and help us maintain our basic sense of what it means to be human, what it means to be safe. Of course, neither toilet paper nor guns will solve the problems this pandemic is forcing us to face, but they are the among the few means of solace we have available.

As we rush to protect our future, as we try to manage our fears, we also need to ask ourselves what the hoarding of resources might be costing others. Sometimes, safety is not about how we provision ourselves as individuals, but how we consider and care for the collective. Reaching out to one another—even from a distance—and sharing what we have might, in fact, be the best way to fulfill our most basic human needs. And it’s the only way we can ever hope to reach Maslow’s third level of love and belonging.