被人忽视的S型弯道:现代厕所的开端

How the humble S-bend made modern toilets possible

By Tim Harford

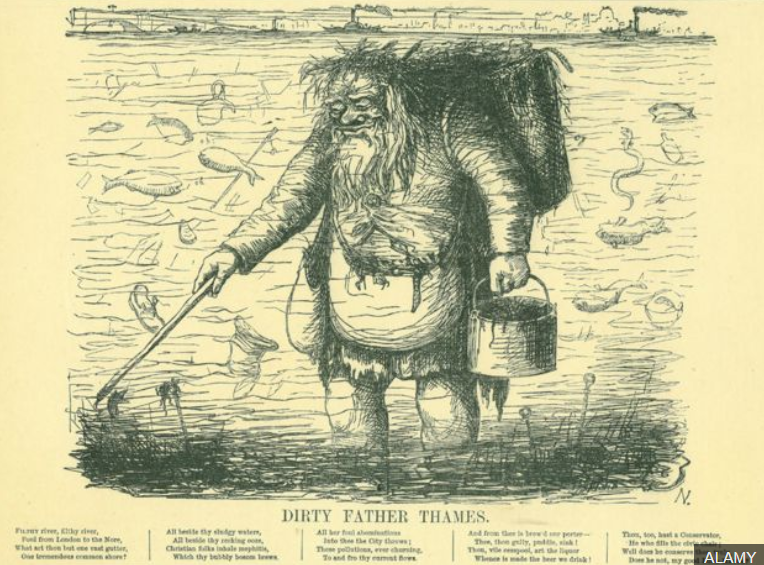

"Gentility of speech is at an end," thundered an editorial in London's City Press, in 1858. "It stinks!"

The stink in question was partly metaphorical: politicians were failing to tackle an obvious problem.

As its population grew, London's system for disposing of human waste became woefully inadequate. To relieve pressure on cess pits - which were prone to leaking, overflowing, and belching explosive methane - the authorities had instead started encouraging sewage into gullies.

However, this created a different issue: the gullies were originally intended for only rainwater, and emptied directly into the River Thames.

That was the literal stink - the Thames became an open sewer.

Cholera was rife. One outbreak killed 14,000 Londoners - nearly one in every 100.

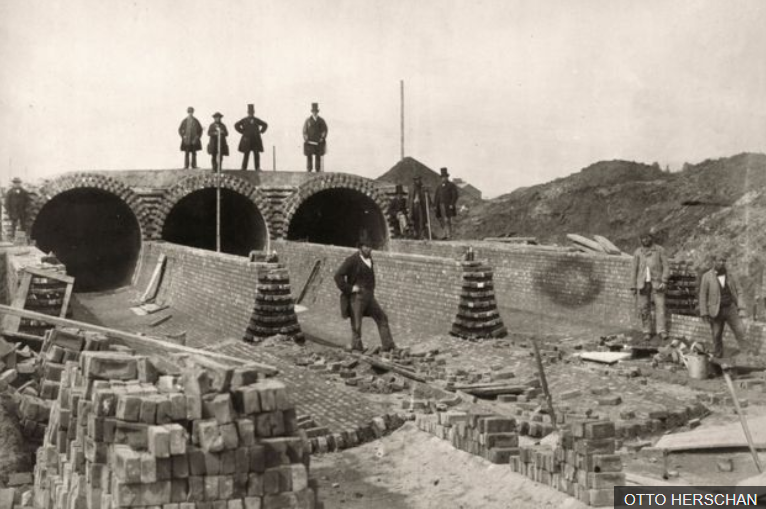

Civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette drew up plans for new, closed sewers to pump the waste far from the city. It was this project that politicians came under pressure to approve.

The sweltering-hot summer of 1858 had made London's malodorous river impossible to politely ignore, or to discuss obliquely with "gentility of speech". The heatwave became popularly known as the "Great Stink".

Unlikely figure

If you live in a city with modern sanitation, it's hard to imagine daily life being permeated with the suffocating stench of human excrement.

For that, we have a number of people to thank - but perhaps none more so than the unlikely figure of Alexander Cumming.

A watchmaker in London a century before the Great Stink, Cumming won renown for his mastery of intricate mechanics.

King George III commissioned him to make an elaborate instrument for recording atmospheric pressure, and he pioneered the microtome, a device for cutting ultra-fine slivers of wood for microscopic analysis.

But Cumming's world-changing invention owed nothing to precision engineering. It was a bit of pipe with a curve in it.

In 1775, Cumming patented the S-bend. This became the missing ingredient to create the flushing toilet - and, with it, public sanitation as we know it.

Simplicity

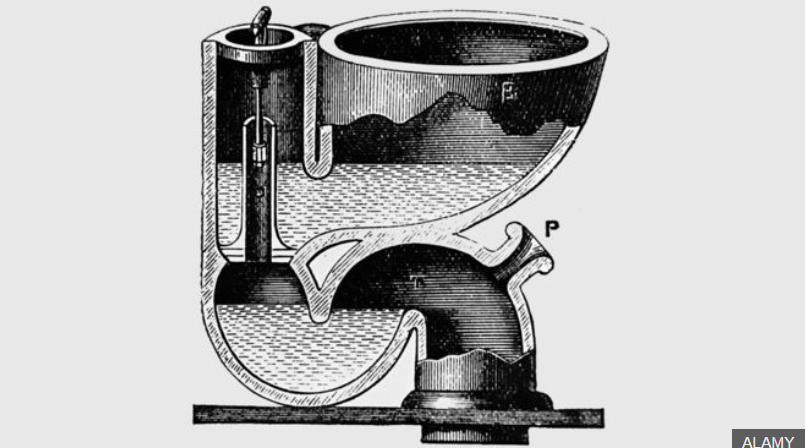

Flushing toilets had previously foundered on the problem of smell: the pipe that connects the toilet to the sewer, allowing urine and faeces to be flushed away, will also also let sewer odours waft back up - unless you can create some kind of airtight seal.

Cumming's solution was simplicity itself: bend the pipe. Water settles in the dip, stopping smells coming up; flushing the toilet replenishes the water.

While we've moved on alphabetically from the S-bend to the U-bend, flushing toilets still deploy the same insight.

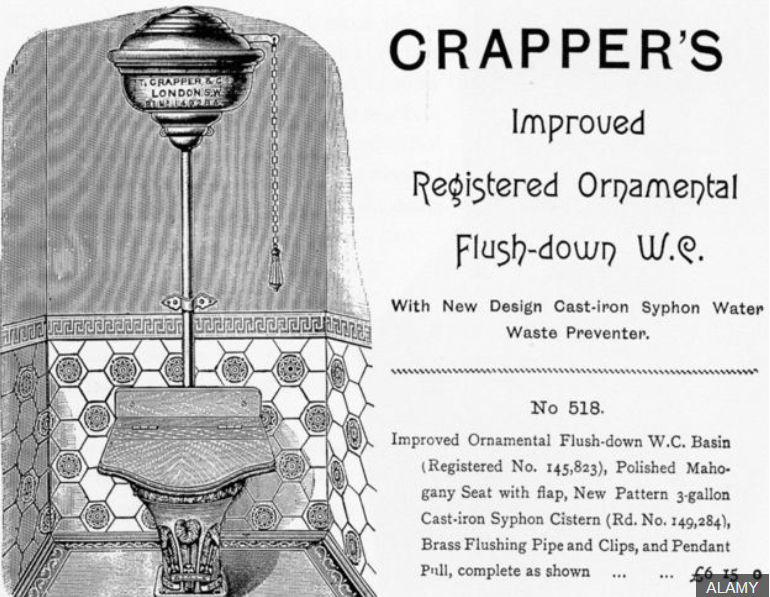

Rollout, however, came slowly: by 1851, flushing toilets remained novel enough in London to cause mass excitement when introduced at the Great Exhibition in Crystal Palace.

Use of the facilities cost one penny, giving the English language one of its enduring euphemisms for emptying one's bladder, "to spend a penny".

Hundreds of thousands of Londoners queued for the opportunity to relieve themselves while marvelling at the miracles of modern plumbing.

If the Great Exhibition gave Londoners a vision of how public sanitation could be - clean, and smell-free - no doubt that added to the weight of popular discontent as politicians dragged their heels over finding the funds for Joseph Bazalgette's planned sewers.

More than 170 years later, about two-thirds of the world's people have access to what's called "improved sanitation", according to the World Health Organization, up from about a quarter in 1980.

That's a big step forward.

Economic cost

But that still means two and a half billion people don't have access to it, and "improved sanitation" itself is a relatively low bar.

It "hygienically separates human excreta from human contact", but it doesn't necessarily treat the sewage itself.

Fewer than half the world's people have access to sanitation systems that do that.

The economic costs of this ongoing failure to roll out proper sanitation are many and varied, from health care for diarrhoeal diseases to foregone revenue from hygiene-conscious tourists.

The World Bank's Economics of Sanitation Initiative has tried to tot up the price tag.

Across various African countries, for example, it reckons inadequate sanitation lops one or two percentage points off gross domestic product (GDP), in India and Bangladesh over 6%, and in Cambodia 7%.

That soon adds up.

The challenge is that public sanitation isn't something the market necessarily provides. Toilets cost money, but defecating in the street is free.

'Positive externality'

If I install a toilet, I bear all the costs, while the benefits of the cleaner street are felt by everyone.

In economic parlance, that's a "positive externality" - and goods that have positive externalities tend to be bought at a slower pace than society, as a whole, would prefer.

The most striking example is the "flying toilet" system of Kibera, in Nairobi, Kenya.

The flying toilet works like this: you defecate into a plastic bag, and then in the middle of the night, whirl the bag around your head and hurl it as far away as possible.

Replacing a flying toilet with a flushing toilet provides benefits to the toilet owner - but you can bet that the neighbours would appreciate it, too.

Contrast, say, the mobile phone. That also costs money, but its benefits accrue largely to me. That's one reason why, although the S-bend has been around for 10 times as long as the mobile phone, many more people already own a mobile phone than a flushing toilet.

If you want to buy a flushing toilet, it also helps if there's a system of sewers to plumb it into, and creating one is a major undertaking - financially and logistically.

When Joseph Bazalgette finally got the cash to build London's sewers, they took 10 years to complete and necessitated digging up 2.5 million cubic metres (88 million cubic ft) of earth.

Because of the externality problem, such a project might not appeal to private investors: it tends to require determined politicians, willing taxpayers and well-functioning municipal governments.

And those, it seems, are in short supply. According to a study published in 2011, just 6% of India's towns and cities have succeeded in building even a partial network of sewers. The capacity for delay seems almost unlimited.

Geographical quirk

London's lawmakers likewise procrastinated- but when they finally acted, they didn't hang about. As Stephen Halliday recounts in his book The Great Stink of London, it took just 18 days to rush through the necessary legislation for Bazalgette's plans. What explains this sudden, impressive alacrity?

A quirk of geography: London's Parliament building is located right next to the River Thames.

Officials tried to shield lawmakers from the Great Stink, soaking the curtains in chloride of lime in a bid to mask the stench.

But it was no use. Try as they might, the politicians couldn't ignore it.

The Times described, with a note of grim satisfaction, how MPs had been seen abandoning the building's library, "each gentleman with a handkerchief to his nose".

If only concentrating politicians' minds was always that easy.