随着年龄增长,性格会变吗?

How your personality changes as you age

By Zaria Gorvett

Our personalities were long thought to be fixed by the time we reach our 30s, but the latest research suggests they change throughout our lives – and bring some surprising benefits.

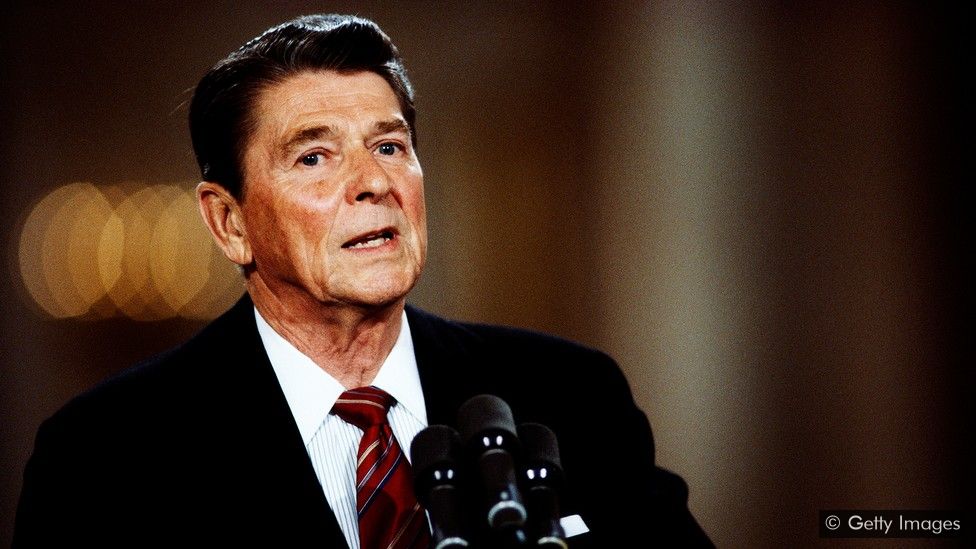

“Mr President, I want to raise an issue that I think has been lurking out there for two or three weeks and cast it specifically in national security terms…” said the journalist Henry Trewhitt, as he locked President Ronald Reagan with a steady, serious gaze.

It was October 1984 and Reagan was on the debating circuit, battling to remain in office for a second term. He had already performed poorly against his main rival a few weeks earlier. Now there were whispers that, at 73 years old, he was simply too old for the job.

After all, at the time, Reagan was already the oldest US President in history. His predecessor had gone for days without sleep during the Cuban missile crisis. Trewhitt wanted to know: did Regan have any doubts that he could function in such circumstances?

“Not at all, Mr Trehwitt,” replied Reagan, holding back a smile. “And I want you to know that also I will not make age an issue of this campaign – I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” His response was met with raucous laughter and applause – and preceded a landslide victory in the election.

Reagan’s quip, however, held more truth than he knew. He didn’t just have experience on his side, he would also have had a “mature personality”.

We’re all familiar with the physical transformation that ageing brings: the skin loses its elasticity, the gums recede, our noses grow, hairs sprout up in peculiar places – while also disappearing entirely from others – and those precious inches of height to which we cling start to slink away.

Now, after decades of research into the effects of ageing, scientists are uncovering another, more mysterious change.

“The conclusion is exactly this: that we are not the same person for the whole of our life,” says René Mõttus, a psychologist from the University of Edinburgh.

Far from being fixed in childhood, or around the age of 30 – as experts thought for years – it seems that our personalities are fluid and malleable

Most of us would like to think of our personalities as relatively stable throughout our lives. But research suggests this is not the case. Our traits are ever shifting, and by the time we’re in our 70s and 80s, we’ve undergone a significant transformation. And while we’re used to couching ageing in terms of deterioration and decline, the gradual modification of our personalities has some surprising upsides.

We become more conscientious and agreeable, and less neurotic. The levels of the “Dark Triad” personality traits, Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy also tend to go down – and with them, our risk of antisocial behaviours such as crime and substance abuse.

Research has shown that we develop into more altruistic and trusting individuals. Our willpower increases and we develop a better sense of humour. Finally, the elderly have more control over their emotions. It’s arguably a winning combination – and one which suggests that the stereotype of older people as grumpy and curmudgeonly needs some revision.

Far from being fixed in childhood, or around the age of 30 – as experts thought for years – it seems that our personalities are fluid and malleable. “People become nicer and more socially adapted,” says Mõttus. “They’re increasingly able to balance their own expectations of life with societal demands.”

Psychologists call the process of change that occurs as we age “personality maturation”. It’s a gradual, imperceptible change that begins in our teenage years and continues into at least our eighth decade on the planet. Intriguingly, it seems to be universal: the trend is seen across all human cultures, from Guatemala to India.

“Generally it's controversial to put value judgments on these personality changes,” says Rodica Damian, a social psychologist at the University of Houston. “But at the same time we do have evidence that they’re beneficial.” For example, low emotional stability has been linked to mental health problems, higher mortality rates, and divorce. Meanwhile, she explains that the partner of someone with high conscientiousness will probably be happier, because they’re more likely to do dishes on time, and less likely to cheat on their partner.

It would be reasonable to think that this continual process of change would make the concept of personality fairly meaningless. But that’s not entirely true. That’s because there are two aspects to personality change: average changes, and relative changes. It turns out that, while our personalities shift in a certain direction as we age, what we’re like relative to other people in the same age group tends to remain fairly stable.

For example, a person’s level of neuroticism is likely to go down overall, but the most neurotic 11-year-olds are generally still the most neurotic 81-year-olds. These rankings are our most enduring characteristics, and distinguish us from everyone else.

“There is a core of who we are in the sense that we do maintain our rankings relative to other people to some extent,” says Damian. “But relative to ourselves, our personalities are not set in stone – we can change.”

Research into Japanese centenarians has found that they tend to score highly for conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness

How do these personality changes develop? “This is the big debate in the field,” says Mõttus.

Because personality maturation is universal, some scientists think that far from being an accidental side-effect of having had longer to learn the rules, the ways our personalities change might be genetically programmed – perhaps even shaped by evolutionary forces.

On the other hand, some think that our personalities are partly forged by genetic factors, then sculpted by social pressures over the course of our lives. For example, research by Wiebke Bleidorn, a personality psychologist at the University of California, Davis, found that, in cultures where people were expected to grow up more quickly – get married, start working, have adult responsibilities – their personalities tend to mature at a younger age.

“People are just kind of forced to change their behaviour and, over time, to become more responsible. Our personalities change to help us cope with life’s challenges,” says Damian.

But what happens when we reach very old age?

There are two possible ways to study how we change over our lifespan. The first is to take a large group of people of lots of different ages, and then look to see how their personalities are different. One problem with this strategy is that it is easy to accidentally mistake generational traits that have been sculpted by the culture of a particular time period – such as prudishness or an inexplicable adoration of custard creams and sherry – for changes that occur as you age.

The alternative is to take the same group of people and follow them as they grow up.

This is exactly what happened with the Lothian Birth Cohort – a group of people who had their personality traits and intelligence examined in June 1932 or June 1947, when they were still at school. At the time, they were around 11 years old. Together with colleagues from the University of Edinburgh, Mõttus tracked down hundreds of the same people when they were in their 70s or 80s, and gave them two more identical tests, several years apart.

“Because we had two different cohorts of people, and both of them were measured at two occasions, we were able to use both strategies at once,” says Mõttus. This was lucky, because the results were remarkably different for the two generations.

The stereotype of older people as grumpy and curmudgeonly needs some revision

While the younger group’s personalities remained more or less the same overall, the older group’s personality traits begin to shift, so that on average, they became less open and extraverted, as well as less agreeable and conscientious. The beneficial changes that had been occurring throughout their lives started to reverse.

“I think this makes sense, because in old age things start happening to people at a faster pace,” says Mõttus, who points out that these people’s health might have been in decline, and they’re likely to have started losing friends and relatives. “This has some impact on their active engagement with the world.”

No one has yet looked at whether this trend would continue into our 100s. Research into Japanese centenarians has found that they tend to score highly for conscientiousness, extraversion, and openness, but they may have had more of these characteristics to begin with – perhaps this even contributed to their longevity.

In fact, our personalities are intrinsically linked to our wellbeing as we age. For example, those with higher self-control are more likely to be healthy in later life, women with higher levels of neuroticism are more likely to experience symptoms during the menopause, and a degree of narcissism has been associated with lower rates of loneliness, which itself is a risk factor for an earlier death.

In the future, understanding how certain traits are linked to our health – and how we can expect our personalities to evolve throughout our lifespan – might help to predict who is most at risk of certain health problems, and intervene.

But there’s another benefit to the research. “I was just giving a talk in a prison yesterday,” says Mõttus. “There was one question they were really interested in: do people change at all? Well the big-picture finding is that yes, they do.” This means that, as far as he is concerned, there isn’t any strong evidence to suggest that people can use their personality as an excuse for their behaviour.

The knowledge that our personalities change throughout our lives, whether we want them to or not, is useful evidence of how malleable they are. “It's important that we know this,” says Damian. “For a long time, people thought they didn’t. Now we’re seeing that our personalities can adapt, and this helps us to cope with the challenges that life throws at us.”

If nothing else, it gives us all something to look forward to as we get older, and find out who we will become.