有声读物: 你不读的书正在兴起

By Clare Thorp

Audiobooks are having a moment. As they soar in popularity, they are becoming increasingly creative – is the book you listen to now an artform in its own right, asks Clare Thorp.

Back in 1878, shortly after he had invented the phonograph, Thomas Edison hit upon an idea. Leaning over his new machine one day he recited the words: “Mary had a little lamb. Its fleece was white as snow.” As he created the first ever audio of the spoken word, Edison dreamed that the technology might one day allow a whole novel to be recorded. Fast forward nearly 150 years, and he’d be pretty impressed to find more than 400,000 audiobooks available to download straight into his pocket.

Audiobooks are in the midst of a boom, with Deloitte predicting that the global market will grow by 25 per cent in 2020 to US$3.5 billion (£2.6 billion). Compared with physical book sales, audio is the baby of the publishing world, but it is growing up fast. Gone are the days of dusty cassette box-sets and stuffily-read versions of the classics. Now audiobooks draw A-list talent – think Elisabeth Moss reading The Handmaid’s Tale, Meryl Streep narrating Charlotte’s Web or Michelle Obama reading all 19 hours of her own memoir, Becoming. There are hugely ambitious productions using ensemble casts (the audio of George Saunders’ Booker Prize-winning Lincoln in the Bardo features 166 different narrators), specially created soundscapes and technological advances such as surround-sound 3D audio. Some authors are even skipping print and writing exclusive audio content.

Audiobooks are attracting A-list stars such as Elisabeth Moss (Credit: Getty Images)

Audiobooks are attracting A-list stars such as Elisabeth Moss (Credit: Getty Images)

For the publishing industry, which has faced its fair share of gloomy news stories over the past two decades, the boom in audio is widely regarded as good news. “It’s the blue-eyed boy of publishing at the moment,” explains Fionnuala Barrett, editorial director of Audio at Harper Collins. “Nobody is running scared from it, in comparison to the similar moment for ebooks where there was that fear that they were cannibalising other formats in the book world. With audiobooks, there’s a feeling that it’s an additive.”

While audiobook sales are up and physical book sales down, it’s not a given that the two things are related. In fact, audio is pulling in new audiences – whether that’s listeners who don’t usually buy books, or readers listening to genres in audio format that they wouldn’t pick up in print.

Research by Nielsen Book found downloads of audiobooks in the UK were particularly high among urban-dwelling males aged 25 to 44. Laurence Howell, content director at Audible – the Amazon-owned audiobook platform – says they’ve also seen big growth in the 18-to-24 age group. “This is not an age group that is traditionally a strong book-buying group.” A study by The Publisher’s Association found 54 per cent of UK audiobook buyers listen to them for their convenience, while 41 per cent choose the format because it allows them to consume books when reading print isn’t possible.

All ears

There is much debate about whether listening to a book is the same as reading it, but perhaps that misses the point. “Often audio is not competing with time spent with books,” says Richard Lennon, publisher at Penguin Audio. “It’s people who are either fitting books and authors into their day in new ways, so people who might be existing readers but have found that during their commute or exercising or cooking dinner, there’s an opportunity to listen. Or it’s an alternative to TV for people who are conscious of their screen time. The really exciting audience for me is people for whom reading and books are not fundamentally part of their lives.”

There’s a real enthusiasm around the opportunity to do exciting, creative things, and broaden the audience for books – Richard Lennon

The booming popularity of audiobooks coincides with the rise of podcasts, and shows an increasing thirst for audio content, which has led to publishers ploughing resources into the format, building dedicated teams and creating in-house studios in order to produce increasingly creative and ambitious listening experiences. “We’ve invested a lot in audio over the last few years,” says Lennon. “There’s a real enthusiasm around the opportunity to do exciting, creative things, and broaden the audience for books. Our approach to it has been to think about how we can keep pushing the listening experience further and further.”

Illustrated poetry collection The Lost Words was brought to audio in the form of recordings made in the British countryside (Credit: Penguin)

Illustrated poetry collection The Lost Words was brought to audio in the form of recordings made in the British countryside (Credit: Penguin)

Lennon says there are now books being recorded that would never have been considered as audiobooks 10 years ago. He points to Robert MacFarlane and Jackie Morris’s book The Lost Words, a beautifully illustrated collection of poems based on words that have disappeared from the Oxford Junior Dictionary. Such a visual work wasn’t an obvious choice to transfer to audiobook, but Penguin commissioned sound recordist Chris Watson, who has worked with David Attenborough. “We captured original wild track recordings out in the British countryside, and built a soundscape that goes under each poem. When Benjamin Zephaniah reads a poem called Blue Bell, the recording under that is a bluebell wood in Thorpeness in the middle of a rainstorm.”

The end product won a Gold Award at the New York Festivals Radio Awards. “To me, it speaks to the level of creativity going into audiobooks at the moment,” says Lennon. “And we’re not the only people doing it. There are loads of brilliant people doing really creative audio publishing.”

In their own words

While some audio versions of books present challenges, others offer obvious advantages. The recent audiobook version of The Only Plane in The Sky, Garrett Graff’s extensive oral history of 9/11, involved a cast of 45, including many of the real people featured in the book, along with raw audio footage from the day itself. The audiobook of Malcolm Gladwell’s recent release, Talking To Strangers – which Gladwell says is outselling the print version by two to one – also used original archival interviews, blurring the line between podcast and book. Gladwell’s success in audio fits with a wider trend of non-fiction doing especially well in an audio format.

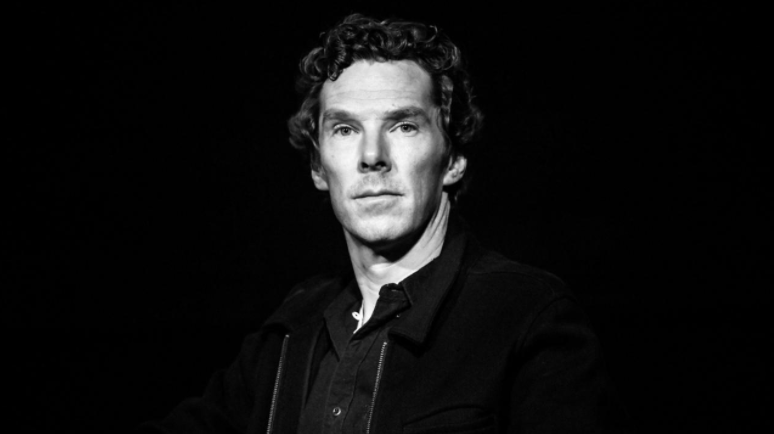

Even the densest of subjects are finding audio success – sometimes given a helping hand by a well-known narrator. Benedict Cumberbatch’s reading of Carlo Rovelli’s The Order of Time no doubt attracted a few listeners who might not normally opt for a book about quantum physics. “Not that long ago, a book on theoretical physics would likely not have been released in audio at all,” says Lennon. “It certainly wouldn't have been read by somebody of that sort of level of fame.”

Benedict Cumberbatch read a four-hour audiobook of The Order of Time, a book about quantum physics (Credit: Getty Images)

Benedict Cumberbatch read a four-hour audiobook of The Order of Time, a book about quantum physics (Credit: Getty Images)

The increased profile of audiobooks also means that more A-list talent is willing to be involved. Earlier this year, Penguin released 30 of their classics in audiobook format, narrated by well-known names including Andrew Scott reading The Dubliners and Natalie Dormer voicing A Room of One’s Own. Meanwhile, Audible has had match-ups including Rosamund Pike reading Pride and Prejudice and Thandie Newton narrating Jane Eyre. A huge seller for them has been Stephen Fry’s 72-hour-long reading of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes: The Definitive Collection.

Listening to the dulcet tones of a familiar voice is an appealing way to work our way through those books we’ve always meant to get around to, but haven’t

Classic titles have proved popular in audible format, perhaps because listening to the dulcet tones of a familiar voice is an appealing way to work our way through those books we’ve always meant to get around to, but haven’t. BBC Sounds recently added unabridged versions of 20 classic novels, including Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Gulliver’s Travels. “Classics are also a nice entry level for people who maybe aren’t sure of audio,” says Howell.

For those just discovering the format, their first experience can be a crucial one. “For people who are relatively new to audio, the voice is absolutely make or break, so getting the casting right is a huge responsibility,” says Fionnuala Barrett. She recently secured father-and-son actors Timothy and Samuel West to read the audio edition of a new JRR Tolkien book, Fall of Gondolin, edited by Tolkien’s son Christopher. “They flip it so Timothy West reads the parts of Christopher, who is now in his 90s, but you can hear that they’re related in their voices and there is something very moving about that. It’s a really good instance of what audio can bring to a project.”

The Fall of Gondolin was JRR Tolkien’s first Middle Earth story; he began writing it in 1917 on the back of a sheet of military marching music (Credit: Alamy)

The Fall of Gondolin was JRR Tolkien’s first Middle Earth story; he began writing it in 1917 on the back of a sheet of military marching music (Credit: Alamy)

While looking for A-list talent to narrate a book is always tempting, big names only work if they have a genuine connection with the material, she says. “For me, I would much rather get somebody who isn’t a household name but is absolutely bang on. When you’ve got the right voice on a particular text, it’s just magic to listen to.” Narrators themselves often accrue fans, who follow them from book to book.

Authors themselves are also getting much more involved in the casting process. “There seems to be a much greater embrace of audio right from the start now with authors, which is really exciting because it turns it into a collaborative casting process,” says Barrett. Some are even writing with the audio version in mind. Ben Aaronovitch, author of the Rivers of London fantasy series, has admitted that he now has actor Kobna Holdbrook-Smith’s version of his characters in his head when he writes.

Others are writing audio-only content. Michael Lewis, Adam Kay, Jon Ronson, Joanne Harris and Phillip Pullman have all written original works for Audible. “For them, I think it’s an exciting opportunity to try creative writing but in a different format, thinking about audio and how your story will resonate to the listener,” says Howell. Original content is now a major focus for the platform, which is also working with playwrights to create new dramas. “Access to theatre can still be fairly limited, and I think a lot of playwrights are excited about the opportunity to reach out to new audiences through audio.”

For Richard Lennon, there is as much excitement to be found in raiding the catalogue, and creating audiobooks for authors and texts who have never been on tape before. “You have the kid-in-the-sweet-shop moment of being able to create recordings of some of these really wonderfully iconic things that have never been done.”

So what of the future? Barrett thinks we’re only just beginning to see the potential of audio as an artform. “We’ve reached that tipping point where it’s getting to be fairly mainstream, but the artistry element is still all to play for. We’re in the kind of ‘planting the flag in the sand’ stage when it comes to ambitious productions.” And what of the people who still think they’re not ‘proper’ books? “The people that are sniffy about them are the people who will be sniffy about anything. I’m not overly perturbed by that.”