小说最好的开场白是什么?

What are the best first lines in fiction?

By Hephzibah Anderson

From the pithy to the provocative, the classic book opener comes in many different forms. Hephzibah Anderson explores the art of the perfect first sentence.

How many times have I rewritten this opening sentence? The first line can be a beast to get right whether you’re composing a dating profile or drafting a workplace pitch – but when it comes to longform fiction, the stakes are vertiginous. Think of all that goes into writing a novel, from conception to final edit and beyond; then picture a prospective reader, besieged by competing demands from rival books, never mind films and binge-worthy boxsets. Imagine next that reader miraculously reaching for our author’s work, scanning its jacket blurb, opening the cover... Connections don’t come much more intimate than that between an author and their reader, and the first sentence is the writer’s chance to woo. Make it enticing enough – pack in sufficient intrigue, atmosphere and character, and do so in a voice that’s compelling enough – and the reader will read on. It’s no wonder Stephen King still spends months, sometimes years, getting his opening salvo exactly right.

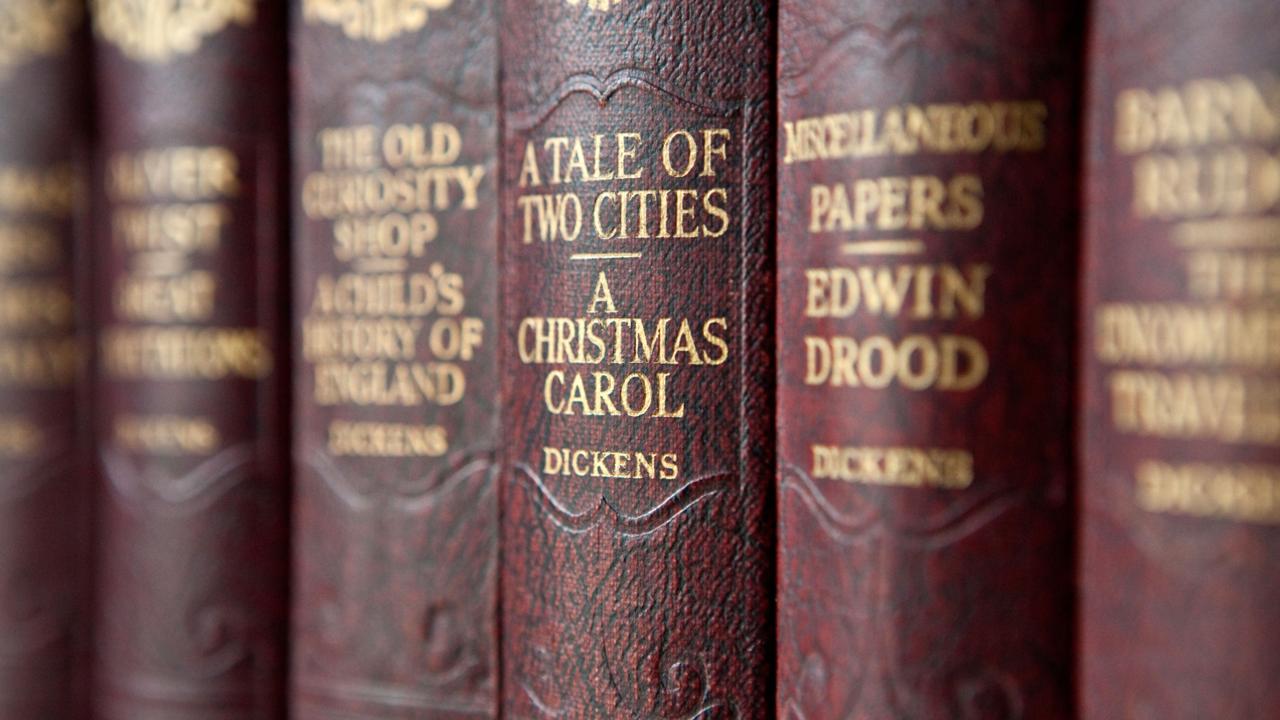

One writer who pulled off a hat-trick of near-ideal openers is Charles Dickens. There’s David Copperfield, of course (“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show”), and A Christmas Carol is succinct perfection (“Marley was dead, to begin with”), but the show-stealer remains A Tale of Two Cities. Parodied, imitated, enduringly familiar even to those who’ve never read the novel, the line beginning “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” is a belter. A sustained rhetorical flourish, it primes us for the intensely contradictory world that characterises this story of love and revolution.

We frontload our expectations, insisting that a handful of words must contain the DNA of all that is to come.

A Tale of Two Cities turns 160 this November, but though its first sentence – all 119 words of it – is by far and away its most celebrated feature, beginnings weren’t much dwelled upon when Dickens penned it. The earliest English-language novels tended to favour leisurely, not to say long-winded set-ups, often deferring the start with a preface. Contrast that with a style that’s been dominant for around a century now, of arriving late and dropping the reader into the narrative in medias res – in the middle of things. These days, it’s not just the style of opening sentences that is different, it’s the weight we give them as critics, writers, even readers. We frontload our expectations, insisting that a handful of words must contain the DNA of all that is to come, encapsulating the conflict of a 300-page story.

“It is a truth universally acknowledged…” that Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice opens with a famous first line (Credit: Alamy)

“It is a truth universally acknowledged…” that Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice opens with a famous first line (Credit: Alamy)

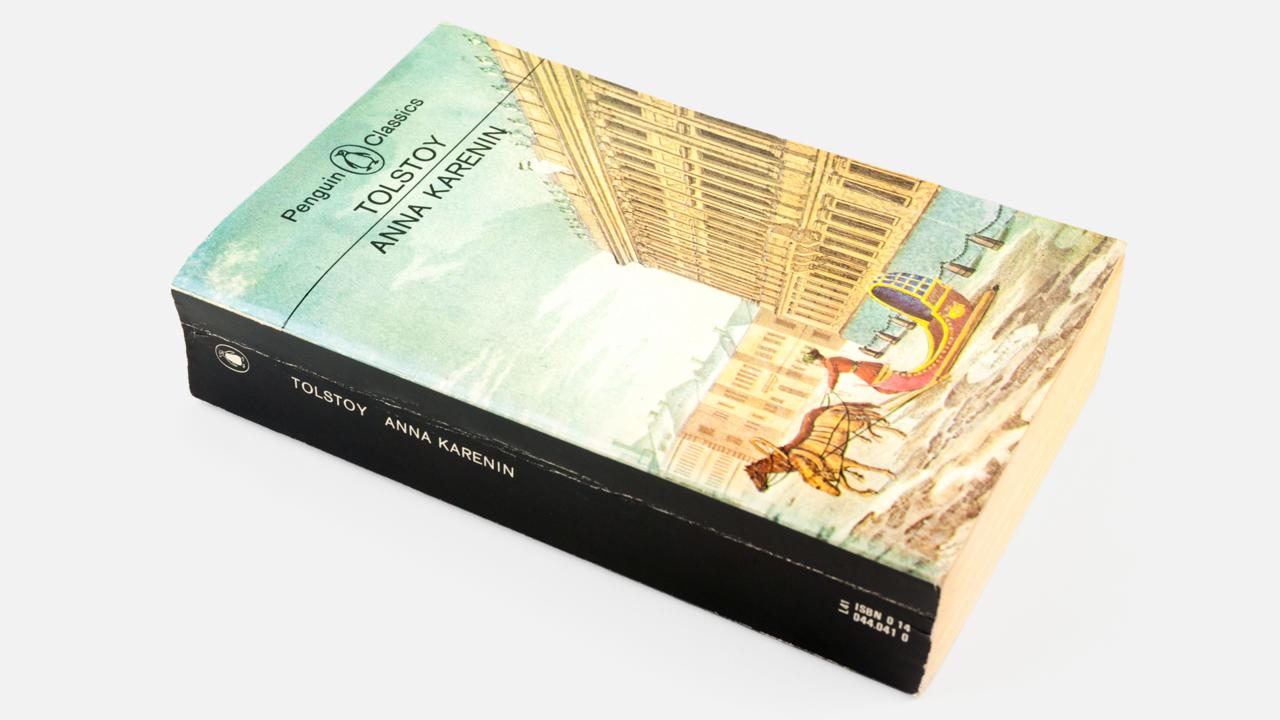

Of course, there are as many ways of beginning a novel as there are novels, and yet themes and trends are there for the spotting. There’s the sweeping statement, for instance, provocative and seductive in its certainty, of which Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is surely the best-known example – “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” . And LP Hartley’s The Go-Between (“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”) adds a plangent note that still reverberates, well over half a century on. Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice – an opener almost as famous as Dickens’ – subverts this epigrammatic set-up with a layer of characteristic irony: “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife”.

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” is the sweeping opening salvo of Anna Karenina (Credit: Alamy)

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” is the sweeping opening salvo of Anna Karenina (Credit: Alamy)

Another approach is to state plain ‘facts’. “I am an invisible man” makes a bluffly apt beginning to Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man. Equally concise is the start of Renata Adler’s cult classic, Speedboat: “Nobody died that year”, a line that instantly prompts questions which can only be answered by reading on. Donna Tartt’s The Secret History manipulates the reader still more deftly: “The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation”.

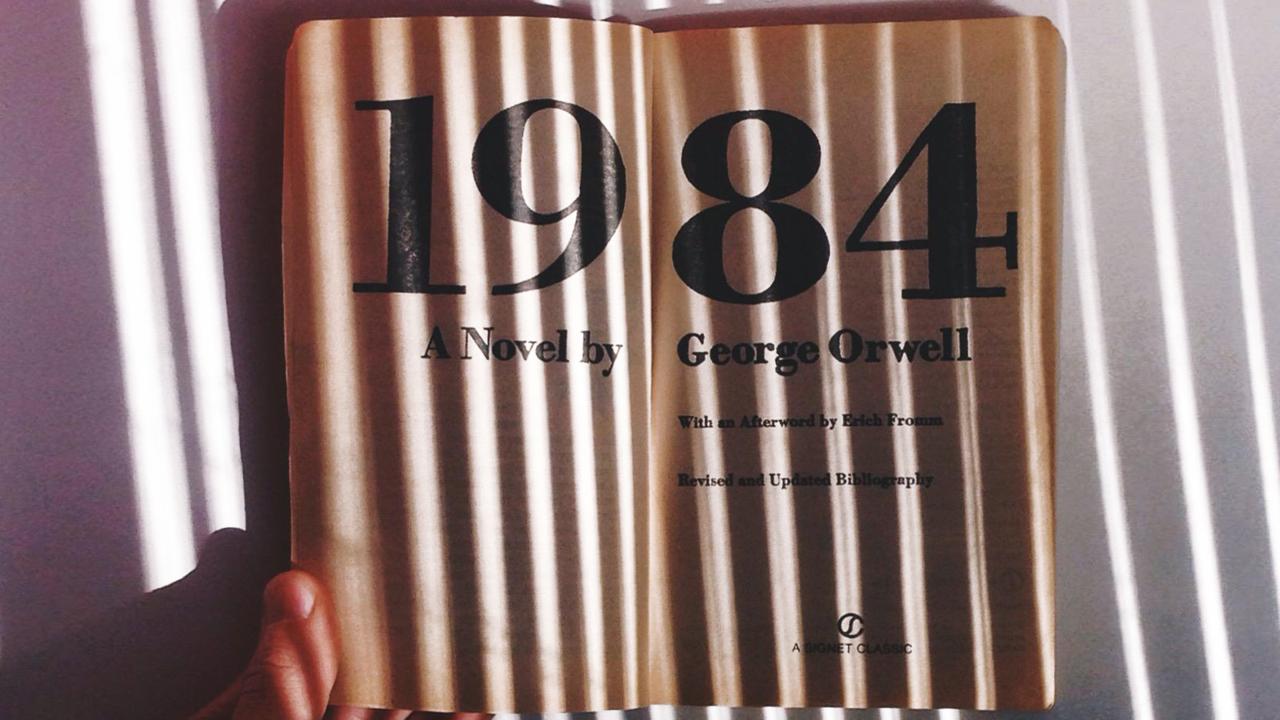

Anomalies can be especially alluring when paired with the humdrum, as George Orwell knew. “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen”, begins Nineteen Eighty-Four. Or how about Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex? “I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day of January 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974”.

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen,” is the arresting opener of Orwell’s 1984 (Credit: Alamy)

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen,” is the arresting opener of Orwell’s 1984 (Credit: Alamy)

Other authors choose to accentuate the fictional nature of their work. Anne Tyler is among the multitude who’ve used the four words that captivate every budding bookworm. “Once upon a time, there was a woman who discovered she had turned into the wrong person,” opens Back When We Were Grownups. Similarly, Annie Proulx nods to her literary forbears when she declares in The Shipping News, “Here is an account of a few years in the life of Quoyle, born in Brooklyn and raised in a shuffle of dreary upstate towns”.

In the mood

And then there’s mood. You’ll read a lot about voice in creative-writing primers but mood can be just as potent, as Proulx’s opening line demonstrates with its “shuffle of dreary upstate towns”. Likewise, the first sentence of Sylvia Plath’s only novel, The Bell Jar, locates its narrative in time, place and, most powerfully, mood: “It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.” Its eerie aimlessness is made still more affecting for having been published less than a month before Plath’s suicide.

“It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs,” is how Plath’s The Bell Jar opens (Credit: Alamy)

“It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs,” is how Plath’s The Bell Jar opens (Credit: Alamy)

The first sentence of The End of the Affair finds Graham Greene ruminating on the very nature of a tale’s start: “A story has no beginning or end; arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead”. Meta much? Well, not compared with Italo Calvino, who started his 1979 novel If on a winter’s night a traveller with the line: “You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveller”.

So what are the rules of writing a great opening line? Unsurprisingly, for writers with talent enough, there are none. Madeleine L’Engle even got away with repurposing a cliché so mocked that the author to whom it’s been attributed (not altogether fairly) now has named after him a prize rewarding the very worst opening. I’m referring to Edward Bulwer-Lytton and the rambling sentence that starts “It was a dark and stormy night…”. In his time, Bulwer-Lytton was more widely read than Dickens, also coining the phrase “the pen is mightier than the sword”, but it’s for his pilloried opener that he’s best remembered, hence San Jose State University’s annual Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest, in which entrants submit dire opening sentences from non-existent works. And yet L’Engle begins her zany – and much praised – YA classic, A Wrinkle in Time, with those same seven words. Fans of Charles M Schulz might recall that Snoopy was also fond of the formulation.

Some of the most celebrated first lines owe their might largely to what follows

Every bibliophile has their own favourite first line (I’m partial to Dodie Smith’s I Capture the Castle, “I write this sitting in the kitchen sink”) and there’s irresistible literary sport to be had from comparing lists. All the same, taking them in isolation does rather miss the point. After all, the chief function of a first sentence is to make you read on. It’s true, too, that some of the most celebrated first lines owe their might largely to what follows. Consider, for instance, Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre: “There was no possibility of taking a walk that day”. As sentences go, its charms are discreet to say the least. And yet those 10 words, as anyone who returns to them having reached the novel’s end, capture so much about its eponymous heroine’s character – her low expectations, her bottomless capacity for disappointment.

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again,” is the intriguing opener of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (Credit: Alamy)

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again,” is the intriguing opener of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (Credit: Alamy)

Shorter by a word is Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again”. Much of what makes it so evocative, so very intriguing, stems from what we subsequently learn about the narrator and Manderley. Since we’re talking length, one of literature’s most famous openers is just three words long. But isn’t part of what makes Herman Melville’s “Call me Ishmael” so startling to do with the digressive – and, yes, impressive – marathon that is the rest of Moby Dick?

There’s a feeling that choosing a book by its opening line is somehow more respectable than judging it by its cover. But both are a form of advertising and just as there’s something to be said for being swayed by a novel’s jacket (an entire team of professionals have laboured to ensure that it sends precisely the right message), so we’d be dolts to place too much emphasis on its opening sentence. After all, some excellent novels have entirely forgettable, if not actively off-putting, first lines. Here’s Ian McEwan’s feted The Child In Time: “Subsidising public transport had long been associated in the minds of both Government and the majority of its public with the denial of individual liberty”.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” is the winning opener of Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (Credit: Alamy)

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” is the winning opener of Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (Credit: Alamy)

It seems fair to say that while we carry the best opening lines around with us, like locket-sized mementoes of dear friends, we are equally prepared to forgive all but the very worst. This isn’t always so with last lines, and there’s a strong case to be made for these being of equal if not greater importance. After all, a reader has invested time, thought and emotion in a book by the time they turn the final page. As for A Tale of Two Cities, no spoiler alerts are required to confirm that Dickens nailed his closing sentence, too: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known”.