自动电饭锅的发明之战

The Battle to Invent the Automatic Rice Cooker

The biggest names in Japanese technology vied to bring them to market.

COOKING RICE ON A STOVETOP can be fraught. Add too much water and you end up with porridge. Without a keen sense of timing, you end up with undercooked grains. But for others, making rice is as easy as pressing a button. In a recent viral video, Malaysian comedian Nigel Ng reacted dramatically to a BBC personality cooking rice with a saucepan rather than using a rice cooker. “World War Two is over, use technology!” he admonished viewers in a follow-up on his Instagram.

He has a point. The automatic rice cooker is a mid-century Japanese invention that made a Sisyphean culinary labor as easy as measuring out grain and water and pressing a button. These devices can seem all-knowing. So long as you add water and rice in the right proportions, it’s nearly impossible to mess up, as the machines stop cooking at exactly the right point for toothsome rice. But creating an automatic rice cooker was not so easy. In fact, it took decades of inventive leaps, undertaken by some of the biggest names in Japanese technology.

For centuries, most Japanese cooks made rice with a kamado, a box-shaped range topped with a heavy iron pot. It was painfully tricky. Cooking rice this way, says columnist and food writer Makiko Itoh, takes heat modulation: high heat until the water and rice boils, then low heat, then high heat again. “And that, with a wood-burning stove, is very difficult.” Each day, Japanese women rose at dawn and labored for several sweaty hours to make rice. (A contemporary restaurant in Nara, Japan, offers a kamado-cooking experience that starts with 15 minutes of pumping a bellows to fan the flames.)

The dawn of the rice cooker, Itoh notes, started in 1923 when Mitsubishi Electric released a simple industrial model. In the 1930s, the Japanese military deployed a multi-cooker for the field. But rice cookers for the home were still years away, and there was a high bar to clear. “With Japanese rice, what you’re looking for is for some of the starch to almost convert to sugar so that it tastes rather sweet,” explains Itoh. Other ideal elements include a sticky texture, separate grains, and a lot of moisture: all hard to obtain, says Itoh, “without any automated way to do it. And people are very, very picky about how their rice should be.”

In 1945, while war-torn Japan faced years of rebuilding, an engineer named Masaru Ibuka opened a radio workshop, choosing as his first headquarters an abandoned telephone-switchboard room in a vacant department store. The next year, Ibuka wrote down the words that would become iconic to the company that in 1958 would become known as Sony: “Purpose of incorporation: Creating an ideal workplace, free, dynamic, joyous.”

However bright the future was, Ibuka’s engineers lived in post-war Japan. Their payment for fixing radios often partly consisted of uncooked rice. This led to the fledgling company’s very first invention. Instead of a sleek radio, it was an electric rice cooker. It was ingenious, but crude: rustic wooden tubs lined with aluminum filaments.

It was a good idea at the time. Most fuel remained expensive, but electricity was relatively plentiful. Ibuka bought a truckload of wooden tubs to turn into rice cookers, and a friend provided the black-market rice needed to test them.

But the finicky devices wouldn’t work unless the rice was consistently of good quality, claimed Ibuka. Iffy rice absorbed water unevenly, making it either flaky and dry, or mushy and broken. “I remember sitting there on the third floor in Shirokiya day after day being fed rice that wasn’t fit to eat,” Ibuka recalled much later. With the tubs lining the walls of their warehouse, Ibuka despaired of ever making a workable device, and went back to fixing radios. While Sony never returned to making rice cookers, their corporate museum in Shinagawa displays the rustic-bucket prototype.

While Sony’s device was a flash in the pan of rice-cooker history, other big names in Japanese electronics pursued the idea. Many released electricity-powered rice cookers, but all had to be constantly monitored. In a word, they weren’t automatic.

It would take a Toshiba salesman to make that happen. In the early 1950s, Shogo Yamada traveled Japan promoting Toshiba’s electric washing machine. Along the way, he asked housewives about their most onerous task. Their answer was cooking rice three times a day, which in some parts of the country was still undertaken with a kamado. When a down-on-his luck maker of water heaters, Yoshitada Minami, came to him looking for work, Yamada passed the project on to him. And since cooking rice was women’s work, Minami passed much of the research on to his wife, Fumiko.

Minami had the mechanical know-how, but Fumiko actually knew how to cook rice. Not only that, but she did so on a traditional kamado stove every day to feed the couple’s six children. To buy time, Minami took out a loan with the family home as collateral, while Fumiko studied the existing electric rice cookers on the market. Generally, when water in a pot of rice has been totally absorbed or evaporated away, the temperature of the container increases rapidly (since the temperature of liquid water generally can’t exceed 100℃, but the temperature of rice certainly can). The secret ingredient turned out to be a bi-metallic switch, provided to Yamada by Toshiba, that would turn the rice cooker off by bending once the temperature in the pot exceeded 100℃.

Fumiko tirelessly tested the prototypes. She cooked rice on the roof, in the sun, and outside during cold mornings. Keeping the pot from releasing heat proved a challenge, until Yamada recalled that in the state of Hokkaido, where winters are brutal, cooking pots were heavily insulated. The final product consisted of two cooking pots, one inside the other, covered in three layers of iron. Toshiba’s automatic rice cooker was finally ready for action.

The gadgets were pricey, which made housewives hesitant to buy them, writes Macnaughtan. But once Yamada, on the road once more, demonstrated how the rice cooker prepared not only rice but also takikomi gohan, a finicky rice dish with a soy-based sauce that often burned, they were hooked. Within the year, Toshiba was producing 200,000 rice cookers every month.

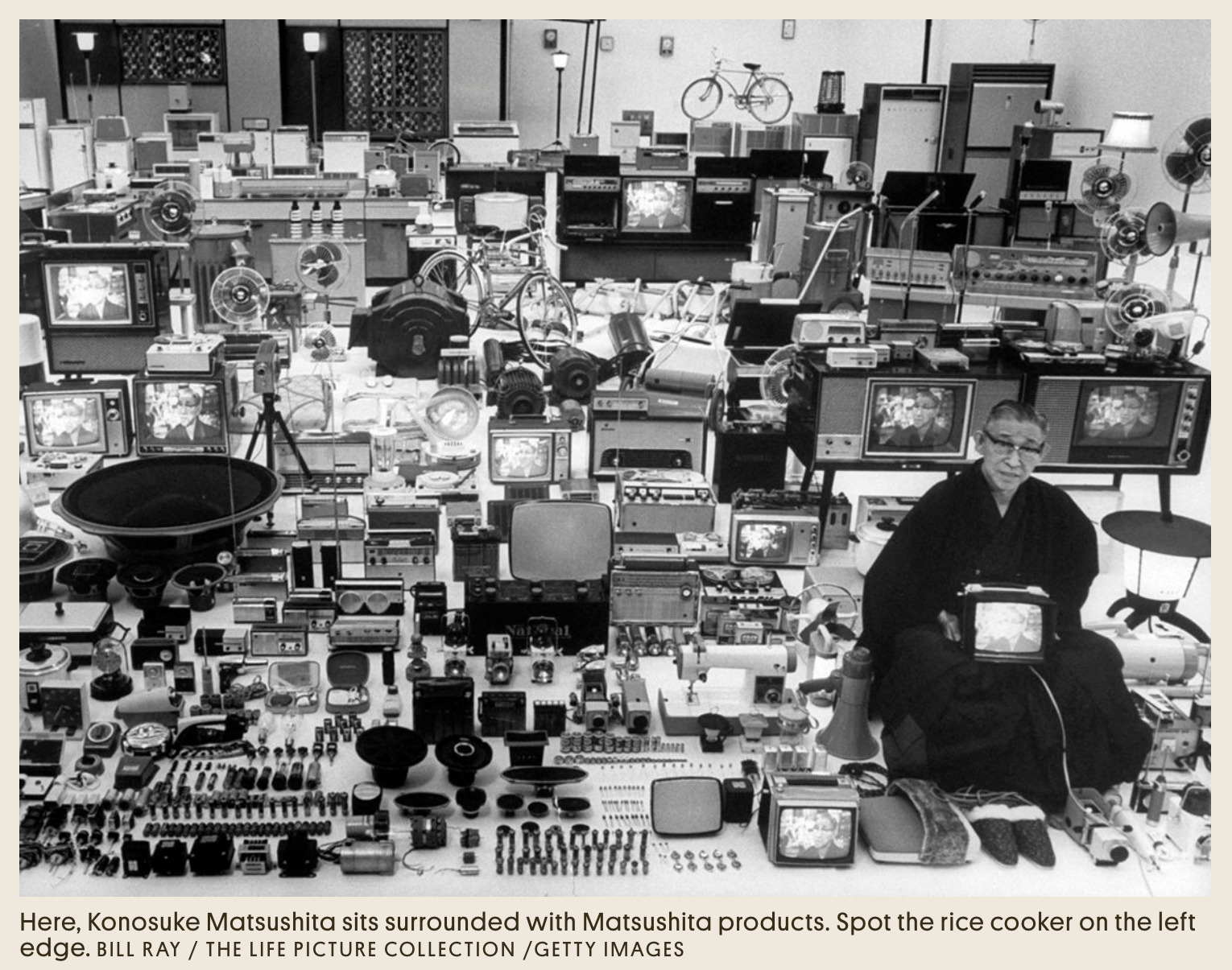

Toshiba’s success, notes marketing professor Kazuo Usui, sparked a rice-cooker manufacturing war. The next year, Matsushita Electric, now better known as Panasonic, jumped into the fray. The company’s employees, writes Yoshiko Nakano in Where There Are Asians, There Are Rice Cookers: How “National” Went Global Via Hong Kong, were horrified that Toshiba had beaten them to the punch. After all, Matsushita was known for their household appliances. “It was therefore seen as a disgrace that such a convenient home appliance as the rice cooker should have come from Toshiba, a manufacturer that was better known for producing industrial machines,” writes Nakano. Matsushita’s president, Konosuke Matsushita, gave one employee such a tongue-lashing that he later feared they’d commit suicide.

That employee, Tatsunosuke Sakamoto, was passionate about rice cookers. His dream, according to Nakano, was to develop an international market for rice-cooking machines. Toshiba had set a clear goal for him to surpass. Matshushita needed to make a rice cooker with only one pot, which would use less metal and result in a cheaper device. Matsushita released their EC-36 rice cooker, with its single pot, in 1956. In 1959, Sakamoto, now head of the company’s Rice Cooker Division, teamed up with William Mong, the Hong Kong-based distributor of Matsushita products. By modifying the rice cooker for Hong Kong consumers, Matsushita learned how to adapt the rice cooker to international tastes, writes Nakano, and took it “to Asia, the Middle East, and Asian diasporas around the world.”

In Japan itself, more than 50 percent of households had an automatic rice cooker within years of its invention. “It absolutely revolutionized women’s work,” says Itoh. “It was one of the main appliances that every woman or every household wanted.” The ads for Toshiba’s first rice cooker emphasized over and over that it would liberate women from “standing or squatting at the kamado, constantly keeping an eye on the rice,” writes Macnaughtan. But while it did stop drudgery over the kamado, the rice cooker wasn’t necessarily a huge win for women’s liberation. Though it may have given some women the time to enter the workforce, at least in a part-time capacity, Macnaughtan concludes that also gave them more time to dedicate to other household chores.

Itoh herself has no need for a rice cooker: She can cook her rice on the stove. “I’ve done it hundreds of times and know what to do!” she says. Ever since the March 2011 earthquake in Japan, she notes, with its ensuing blackouts, many people have tried to rely less on technology and more on their own skills, with some even taking up pickling and growing their own vegetables.

The number of people now learning how to cook rice sans automation is small but significant, she says. “My mother has gone back to doing it that way. My aunt has gone back to doing it that way,” says Itoh. “I don’t grow my own vegetables, but I do cook my own rice.” But there’s no shame in using rice cookers, which even in their simplest forms are an elegant solution to a tricky task. There is shame, though, in not washing your rice before you cook it. You should wash your rice.

更多精彩详细内容请关注小译号Atlas Obscura