Are recessions always a bad thing?

Is there such a thing as a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ recession?

By William Park

How can the economic outlook appear so bleak, while economists remain upbeat? Not all recessions affect people equally.

When the UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced his economic intervention at the beginning of lockdown, the buzzword he kept reaching for was “unprecedented”.

In the second quarter of this year, the US economy shrank by 32.9% – a huge loss, bigger than any decline on record. France, Italy, Germany, Spain; almost every major economy has also seen a big drop in gross domestic product (GDP) at the start of this year. In the UK, in April alone, GDP shrank 20.4% and is on track for the biggest decline in 100 years.

Meanwhile some economists remain upbeat – predicting speedy “v-shaped” recoveries. How can it be that they think the worst economic performance on record is not such a big deal?

GDP doesn’t tell the full story. When the economy tanks, it’s the other things that really hurt – the small businesses that have to fold, taking their owner’s life savings with them; the graduates forced to abandon their dreams, and get an office job instead; the families left trapped with a mortgage to pay and no way to sell their house; the people dealing with the stress of not knowing how to pay their bills or being able to visualise a future. And when it comes to this human cost, all recessions are far from equal.

What makes a recession “good” or “bad” is who it affects and how badly it affects them.

In the last three decades, a recession has come and gone somewhere in the world every couple of years, according to the IMF.

Good or bad?

Bentham previously worked at the Bank of England and before that at EY, one of the “Big Four” accounting firms. She says that banks are much better set up to handle a financial crisis than a decade ago. “Central banks have learned that when there is financial sector turmoil they step in with liquidity, cheap funding, to shore them up,” she says.

Coming into a labour market [during a recession] has long shadows for vulnerable workers, but not for skilled workers – Carol Propper

Unions representing workers in the US car manufacturing industry appealed for a huge multi-billion-dollar bailout in 2008 (Credit: Getty Images)

Unions representing workers in the US car manufacturing industry appealed for a huge multi-billion-dollar bailout in 2008 (Credit: Getty Images)

What is noticeable about this recession is that far more workers are going to be in a vulnerable position if social-distancing rules remain in place long term.

At present the crisis seems to be hitting very much the lower income groups – Carol Propper

“No one is saying the economy has not been hit, it’s just the losses are not yet crystalising,” says Bentham. “People are taking mortgage holidays, credit holidays – it just means the losses are being pushed further down the road. But it will hit. Eventually the financial sector bubble of confidence will burst and we will see real turmoil again.

All shops, restaurants, bars, museums and cinemas in the UK were given the green light to return to business from 4 July. But it isn’t as simple as opening the shutters and welcoming customers back. Cinemas, for example, need to draw customers in with blockbuster movies. But film distributors are holding their cards close to their chest.

Supply vs demand

Demand shocks happen when demand for products drops as people stop earning money.

When oil prices go up, the cost to produce products manufactured with oil increases, and those costs are passed onto the customer

Where are the opportunities?

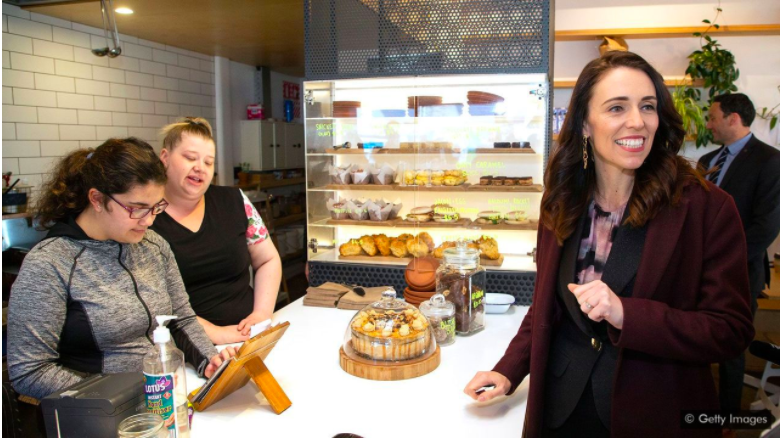

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced a relief bill with social values at its core (Credit: Getty Images)

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern announced a relief bill with social values at its core (Credit: Getty Images)

Bentham, a heterodox economist who considers herself someone who questions the mainstream and looks for more socially focused answers, says that now is the time to fix parts of the economy we don’t like as part of the recovery. “As a woman, things like childcare, caring for sick relatives and lack of funding for social services is a massive drag on the productivity of women. We could reimagine what investment is by building the recovery around services that will improve the productivity of neglected people.”

“We have spent the last hundred years or more thinking the economy is great,” says Bentham, “which we have seen is not true. Money doesn’t trickle down from the top making everyone richer.”

Bentham gives the example of New Zealand’s recovery plan, which references the country’s high rate of incarceration, teenage suicide and the inequality faced by Maori people. “The Covid-19 recovery creates a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to address these inequalities [by reforming the economy],” reads the report.

“New Zealand is making really good progress in terms of not assuming that economic growth means everyone gets wealthier,” says Bentham. “They’re saying ‘Let’s measure it on the basis of human wellbeing and welfare’. This goes back to Aristotle – the economy being about gaining the resources to live a good life and flourish. In their normal lives people are so busy earning money they don’t stop to think what they are earning money for.”

“Clearly one of the things Covid has done is it really exposed the inequality fault lines that exist,” says Propper, who is also the president of the Royal Economics Society. “Partly because individuals that are poorer are more likely to suffer ill health and also work heavily in healthcare.”

Stopping global economies has made governments think about recovery with a green agenda. That, I think, is grounds for optimism – Carol Propper

The recession might also present an opportunity to take meaningful action on climate change. In June, Germany announced a €130bn (£117bn) recovery plan, one-third of which has been specifically set aside for green investments.

The idea of greening the economy in a recovery is not new. Former US President Franklin D Roosevelt’s “New Deal”, the recovery plan from the Great Depression, encouraged the expansion of US National Parks recognising their importance for people’s wellbeing. However, there was also a huge emphasis on road building – something that provided masses of jobs but can hardly be considered green.

“One of the good things about greening the economy, these projects are labour heavy,” says Propper. “Not building wind turbines, but retrofitting houses and redesigning city centres, those kinds of jobs are very labour intensive so they employ lots of people who can learn skills. Plumbers, housebuilders – all of those are useful and transferable skills.

“That, I think, is grounds for optimism,” she says. “Stopping global economies has made governments think about recovery with a green agenda.” Propper warns, however, there needs to be more than lip service paid to addressing inequalities and green industries.

更多精彩内容请关注小译号【BBC】