为什么我们会对特定的动物更加抱有同理心?

Why Do We Feel Compassion and Empathy For Specific Animals?

Written By Marc Bekoff Ph.D.

New research answers critical questions in the study of human-nonhuman animal relationships

A recent paper published in Scientific Reports by Aurélien Miralles, Michel Raymond & Guillaume Lecointre called "Empathy and compassion toward other species decrease with evolutionary divergence time" caught my attention, and I'm glad it did. I found it to be fascinating, methodically sound, and rich in thought. Each time I read it I think of more questions about future research in the ever-growing transdisciplinary area called anthrozoology that focuses on the study of human-nonhuman animal (animal) relationships. I also think many veterinarians will be interested in this seminal research.

When I saw the title I immediately thought of Melanie Joy's Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows: An Introduction to Carnism (in which the emphasis is on so-called "farmed animals") and Hal Herzog's Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It's So Hard to Think Straight About Animals. It also reminded me of an interview I conducted with Kristof Dhont and Gordon Hodson about their unique book titled Why We Love and Exploit Animals: Bridging Insights from Academia and Advocacy.

The research essay, which is available for free online, provides a much more detailed evolutionary (ultimate) explanation than the above sources, which focus more on proximate, or immediate reasons, why we view different animals differently and make inconsistent choices about how we interact with them and use them. For example, why do some people "unmind" cows, pigs, sheep, chickens, and other animals who they choose to eat, while they fully recognize that dogs and other companion animals are sentient, feeling beings, who care what happens to themselves? In fact, they're all mammals who share the same basic neurophysiology and neural anatomical structures that are important in how they experience the same emotions in similar ways. It's essential to remember that cows, pigs, and sheep who are unrelentingly tortured on factory farms are no less sentient than companion dogs or cats.

The evolutionary biology behind the reasons we view different animals differently

For the most part, "Empathy and compassion toward other species decrease with evolutionary divergence time" is a pretty easy read and one can get a lot out of it by reading the introduction, looking at the accompanying figures (some of which are included below), and reading the discussion.

To introduce their essay, Aurélien Miralles and his colleagues begin, "Currently the planet is inhabited by several millions of extremely diversified species. Not all of them arouse emotions of the same nature or intensity in humans. Little is known about the extent of our affective responses toward them and the factors that may explain these differences."

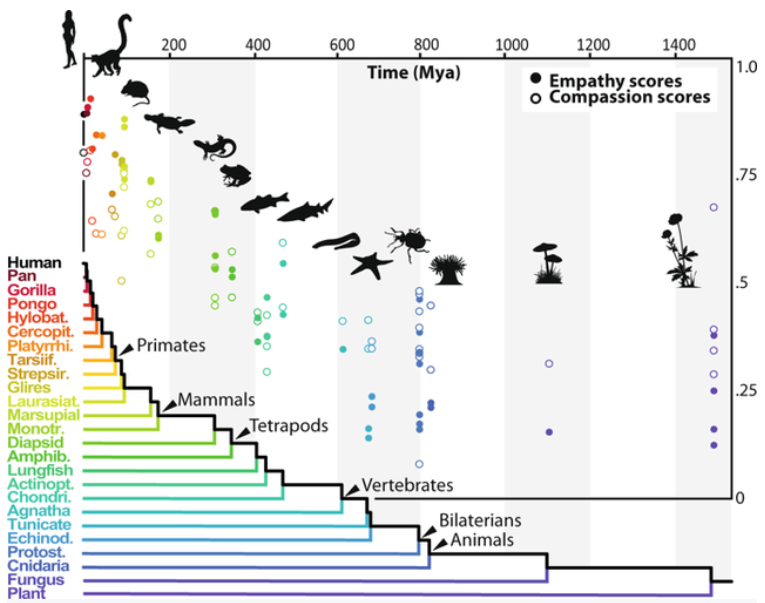

To learn more about why differences in compassion and empathy exist, the researchers conducted an online survey involving 3509 respondents who had to answer questions about their "empathic perceptions or their compassionate reactions toward an extended photographic sampling of organisms." Participants viewed 47 animal species including humans, four plants, and one fungi. Of the 3509 raters, 2347 were used in the final sample (1134 for the empathy test and 1213 for the compassion test).

It's important to understand precisely how this research was carried out and the definitions that were used, I quote directly from their essay. To conduct their study, the researchers write, "The notion of empathy is presently referring to the capability to connect with one another at an emotional level14,17. The driven question proposed to the raters to assess their empathic preferences was 'I feel like I'm better able to understand the feelings or the emotions of [choice among a pair of pictures representing different organisms]'. In contrast, the notion of compassion (also termed empathic concern) has been used here to refer to the feeling of concern for the suffering of others, associated with a motivation to help13,18,19. The corresponding question proposed to raters was "If these two individuals were in danger of death, I will spare the life of [choice among a pair of pictures] as a priorit" (Fig. 1)

It's important to understand precisely how this research was carried out and the definitions that were used, I quote directly from their essay. To conduct their study, the researchers write, "The notion of empathy is presently referring to the capability to connect with one another at an emotional level14,17. The driven question proposed to the raters to assess their empathic preferences was 'I feel like I'm better able to understand the feelings or the emotions of [choice among a pair of pictures representing different organisms]'. In contrast, the notion of compassion (also termed empathic concern) has been used here to refer to the feeling of concern for the suffering of others, associated with a motivation to help13,18,19. The corresponding question proposed to raters was "If these two individuals were in danger of death, I will spare the life of [choice among a pair of pictures] as a priorit" (Fig. 1)

The results of this novel analysis are pretty straightforward (see Figure 2). Concerning empathy, the correlation between empathy scores and the divergence time separating the animals from humans was strongly negative. Likewise, compassion scores were highly correlated with empathy scores and divergence time (see figure 4). However, the correlation with divergence time was lower for compassion scores when compared with empathy scores, with the compassion scores being more related to a person's ethical position on nonhuman animals. They stress, however, that the close relationship between the two scores is important.

The results of this novel analysis are pretty straightforward (see Figure 2). Concerning empathy, the correlation between empathy scores and the divergence time separating the animals from humans was strongly negative. Likewise, compassion scores were highly correlated with empathy scores and divergence time (see figure 4). However, the correlation with divergence time was lower for compassion scores when compared with empathy scores, with the compassion scores being more related to a person's ethical position on nonhuman animals. They stress, however, that the close relationship between the two scores is important.

What does this all mean?

To conclude, the researchers title their discussion "Empathy, resemblance, and relatedness: The anthropomorphic stimuli hypothesis." They write: "Based on our results, we here hypothesize that our ability, real or supposed, to connect emotionally with other organisms would mostly depend on the quantity of external features that can intuitively be perceived as homologous to those of humans. The closer a species is to us phylogenetically, the more we would perceive such signals (and treat them as anthropomorphic stimuli), and the more inclined we would be to adopt a human to human-like empathic attitude toward it."

I look forward to furthering the discussion of this landmark paper and future research on this interesting and important topic. Often, people are hard-pressed to explain why they feel closer to some nonhumans than to others, and this essay opens the door to learning more about these differences. In an increasingly human-dominated world, it's essential to know why humans feel the way they do about the nonhumans with whom we share our magnificent planet. Research in anthrozoology surely will help to provide important and relevant information.